Today is the Feodor Dostoevsky’s 200th birthday. We present this essay on one of his major novels to commemorate the day.

Photo: yablor.ru

Photo: yablor.ru

Did the great writer Feodor Dostoevsky know when he was writing his landmark novel, Demons (also translated as, The Possessed)1 that he was recording a prophecy? This novel astounds its readers again and again with its description of revolutionary forces past, present, and future—descriptions that span a number of levels: psychological, spiritual, and mundane, and the subtle interconnections between each. It is set in the microcosm of a nameless provincial Russian town, but history shows that the blueprint, the seeds, and the mentality are universal. Anyone who wishes to understand how the bloody revolution gained momentum in Russia, and how it could do so anywhere, must definitely read this book.

This topic is enormous, and surprisingly little has been written in English on the subject of revolution and Dostoevsky’s Demons. Needless to say, it was banned after the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, and an aura of prejudice remained around it in the late soviet era. Perhaps in the West, the subtleties are harder to grasp—one needs to understand at least a little the Orthodox Christian soul of Russia. But one sub-theme that is painfully relevant to us everywhere seems to run through the novel, linking the chain of personalities and deeds that lead up to the final breakdown of a once stable society: It is the theme of fatherlessness.

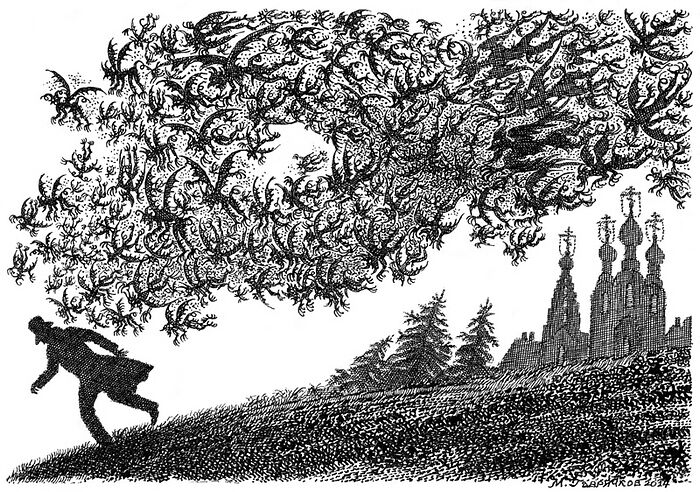

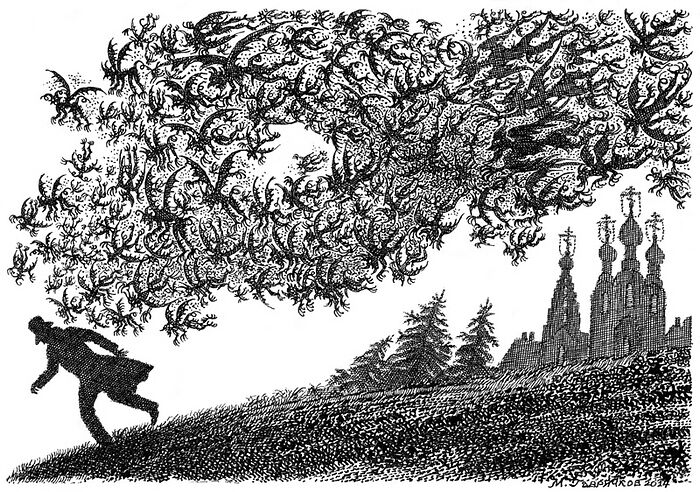

Illustration to Demons by M. Gavrichkov, pen and ink. Photo: fedordostoevsky.ru

Illustration to Demons by M. Gavrichkov, pen and ink. Photo: fedordostoevsky.ru

The phenomenon of fatherlessness has a name in Russian that evokes a whole modern portrait. It is the word, “bezotsovshchina”—bezotsov meaning “without fathers”, with the suffix “-shchina” implying a state or phenomenon. The suffix is usually attached to something negative, or at least nuanced in a negative direction. Demons seems to break the record for its number of pointedly fatherless anti-heroes.

It must first be noted that part of what makes Dostoevsky such an outstanding writer is that there are no unnecessary details, no useless digressions, or picturesque descriptions simply for the sake of beauty (or ugliness) itself. The absence of fathers in the characters’ family is but a passing detail—but an important detail. Even the names are descriptive and indicate to the reader what purpose each character serves in his tightly-woven story.2 We begin with the first character whom the narrator introduces in the novel: Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky.

“In approaching the recent, very strange events that occurred in our hitherto rather unremarkable town, I feel that I must start further back by supplying some facts about the life of the gifted and well-respected Stepan Trofimofich Verkhovensky. This may serve as an introduction to the story to come.” Note that the story begins with Stepan Verkhovensky, whose not irreproachable yet loveable personality is immediately explained by his childhood daydreams of “taking a gallant civic stand”—that is, becoming a romantic, important figure. The narrator points to his role in the future terrible event, but at the same time offers an excuse for him, saying that “after all, his behavior was milder and less offensive, for he was really a very nice man.” This indicates that those to come after him are not nice, mild, men, and were rather more offensive. His surname is also points to the fact that he would be the first in a line of people bearing his "seed"—the root “verkh” indicates “upper” or “over the others”.

Stepan Verkhovensky is described as man of letters, a scholar, who in reality has no academic achievements—something generally overlooked by those in his town, who generally indulge his vanity. He is basically spat out by the revolutionary circles of Herzen and Belinsky because they understand that he hasn’t the real stuff of a revolutionary, but his imagination is able to transform his “exile” from St. Petersburg to this provincial town and general irrelevance into something like martyrdom. His main social coin is his elegance, which was acquired and not inherent, as the narrator shows in a passing remark that could almost go unnoticed: “Verkhovensky felt he had to make a good impression, which should have been easy with his elegant manners. For, although he was, I believe, of humble origin, he had been brought up from earliest boyhood in a well-known Moscow family and spoke French like a native Parisian.” So, Stepan Verkhovensky is also fatherless, otherwise he would not have been brought up in someone else’s family. But that is all we know about his origins. We know that he is basically good and decent, but severed from his real family he grows up nursed on his own daydreams of greatness, a fantasy supported by his highly cultured environment in what was probably a noble family of very old lineage.

Because he grew up in this fantasy world without a real father, he is basically incapable of having a serious family life of his own—only a series of romantic monogamous relationships without any responsibility. The fruit of one of these relationships would become the novel’s main monster, but more about him later.

We find Stepan Verkhovensky in the novel no longer young, and because he has no real achievements, and no real family, he has become the de facto dependent of a wealthy widow—Varvara Petrovna Stavrogina—whose estate is located near the small house he inherited from his first wife. Mrs. Stavrogin hired Stepan as a tutor to her only son, Nicholai, and her other underaged wards.

Mrs. Stavrogin and Stepan Verkhovensky had a “strange relationship”. She became the mother he perhaps never had, but when a man is fifty years old and dependent upon a “mother”, the relationship is bound to be strange. The narrator points out early in the novel that “he had become, above all, a sort of son for her—a creation, her own invention… She had invented him, and she was also the first to believe in her own invention. He was a bit like a part of her private daydream. Consequently, she made great demands upon him, almost making a slave of him.” Varvara Stavrogina also dreamed of becoming an important public figure, and thus she needed this man whose main asset was his learned refinement. Nevertheless, for all the dysfunction in their platonic friendship they were truly, deeply attached to each other, and as the narrator first described it, “Separation is unthinkable because the one who loses his temper and decides to break it up would probably die himself if he went through with it.” So, Varvara Petrovna continually seeks to put Stepan to good use. However, when they go to St. Petersburg to offer their services to the “Cause”, they leave utterly humiliated. The new generation of liberals, spawned by the older generation of liberals, turns out to be completely without any veneer of refinement, and only mock and ridicule their forebears. S. Verkhovensky finds that his supposedly noble ideas have become the “toys of mindless brats”.

Nicolas Stravrogin, Varvara’s son, grew up essentially fatherless. Even when his frivolous father was alive he was estranged from his wife, who was by far the wealthier of the two. Verkhovensky was invited to be Nicholai’s tutor when he was eight years old. With an absent father he was completely under the care of his mother, who “didn’t talk to him much and hardly ever prevented him from doing what he wanted”. She was not the kind of mother who could even have pretended to replace a father, and to make matters worse she tried to fill the gap with Stepan Verkhovensky. “In fairness to Mr. Verkhovensky, it must be said that he knew how to gain the affection of his pupil. His secret was quite simple: he was a child himself.” However, Verkhovensky indulged himself in a way totally impermissible for a professional tutor: He would wake the boy up at night and confide family secrets in him, pour his heart out to him about his own grievances against his mother, and they would sob in each other’s arms. “We may assume that the tutor was to some extent responsible for upsetting his pupil’s nerves…”

Amazingly, Dostoevsky touches here on what is now well known in psychology concerning the psyche of some men who grew up fatherless, and their vulnerability to a father figure, no matter how that figure fails as an example of manhood. “We may assume that the two friends’ tears, when they sobbed in each other’s arms at night, were not always caused by domestic intrigues. Mr. Verkhovensky had managed to touch the deepest-seated chords in the boy’s heart, causing the first, still undefined, sensation of the undying, sacred longing that a superior soul, having once tasted, will never exchange for vulgar satisfaction. (There are even people who value that longing more than the more radical fulfillment, even when it is possible.)” This gives us a hint as to why Nicholai Stravrogin, a handsome, gifted, and elegant man, was not only incapable of loving the women who adored him, but took a certain pleasure in tormenting them. He was guilty of serious crimes and various outrages, but he was never held accountable because no one seemed to be able to decide whether he was a tormented superior soul, mentally ill, or simply an evil man wearing a mask of mystery and elegance.

This unhealthy relationship was observed, and Nicholas was sent to boarding school, where he became even more distant from his mother, who nevertheless sends him all the money he requests. He becomes a reckless, wanton bully who exploits high society women and then insults them publicly. It is in this depraved St. Petersburg period that he takes an action that is interpreted in turns as either noble or base, but around which the entire novel ultimately revolves, and which triggers the tragic finale.

The implications of the surname Stavrogin clearly come to rest in Nicholas. The root “stav” means “to put”, while “rog” means “horn”. These two words together also form an idiom used in reference to marital infidelity.

Having failed miserably in the capital, Stepan Verkhovensky becomes the ideological leader to a group of young people in the province. But soon his real son Peter arrives, and takes what was deemed lofty ideology to its next level, causing great harm to people’s lives and in fact, disrupting the life of this staid provincial town. Peter Verkhovensky was born to Stepan Verkhovensky’s frivolous first wife while the couple was living in Germany. This fact also points to a kind of fatherlessness—Russians often call their country either the Fatherland—Otechesvto, or the Motherland—Rodina. This child was born without a Fatherland, so to speak. Stepan Verkhovensky had sent his little son back to Russia “like a package”, where he was raised in a foster family. He grows up to be precisely what the apostle talks about: “Without natural affection” (Rom. 1:31; 2 Tim. 3:3). If out of Nicholai Stravrogin, Verkhovensky senior’s “foster son”, some noble feeling or passion would occasionally break loose, the senior’s natural son is utterly devoid of any real feeling, never mind anything noble or Christian. To the contrary, he’s like the devil himself. Even the physical description of him given when he appears on the scene as an intruder at a provincial evening gives us the impression of a reptile, a serpent: “No one could say he was bad-looking, yet nobody liked his looks. His head was elongated at the back and seemed compressed at the sides, making his face rather pointed. His forehead was high and narrow and his other features small and fine: a sharp nose and long, thin lips.” He had deep folds on his cheeks and wrinkles on his cheekbones. “He moved and walked hurriedly, even when he wasn’t pressed for time… He spoke rapidly and hurriedly, but with assurance, and without having to search for the right word… One began to imagine that the tongue in his mouth had something special about it, that it was very long and thin, very red, and exceptionally pointed, with a constantly flickering tip.”

Peter Verkhovensky, who openly despises his own father, seems to be seeking a father in Nicholai Stavrogin. Stavrogin is the only person Peter looks up to, even idolizes. Stavrogin is everything Peter is not, and the latter is well aware that his own image is not polished or charismatic enough to take charge of the Cause outside their provincial town. He wants to make Stavrogin the figurehead of a movement Peter would control behind the scenes, and he is even willing to humiliate himself before Stavrogin’s contempt. Peter, like a devil, wants to use Stravrogin as his antichrist.

Of course, the simple fact that Peter Verkhovensky grew up fatherless is not intended to show that fatherlessness is itself an indictment, that such children will always turn out bad. I think that Dostoevsky uses this very negative figure to characterize a revolutionary leader, types he had himself been involved with in his youth, who were basically “spawned” by the previous generation of poetic liberals who had given them no real upbringing, no rootedness, and no faith in God. The result was that many of them became not only atheists, but even antichrists.

Besides, there are two other characters in the novel who would prove that growing up without their natural father did not ruin them completely; however, they do not escape spiritual harm, because only a caring father can completely protect a child from the evils of the world. These are the Shatovs: Ivan Pavlovich and his sister, “Daria (Dasha) Pavlovna. Ivan Shatov was the son of Varvara Petrovna’s valet, and Dasha became her ward. Varvara Petrovna was a complicated woman but very generous. She gave both of these peasant-born children educations and provided for them. Stepan Verkhovensky was also set as a mentor for them, inculcating liberal ideas into Shatov. These ideas would cause him to be expelled from university. He goes down the path of the liberal “Westernizers”, travelling to Europe and entering into a “free-love” marriage with an “emancipated woman”. He even travels to America to see what life is like without a monarchy. After returning to Russia, he completely sheds his revolutionary ideas and begins to earn his own meager living, accepting no more charity from his former benefactors. Stepan Verkhovensky considers him an ungrateful traitor to his ideas, saying that he is constantly shouting about “Holy Mother Russia—notre sainte Russie.” He supposes that it’s due to the violent upheaval in his personal life: His wife had amicably parted with him to pursue “freedom”, only to be abused by Stavrogin abroad. But the story shows that Shatov’s change of heart and return to his roots is more complex and profound—and he ultimately suffers for it.

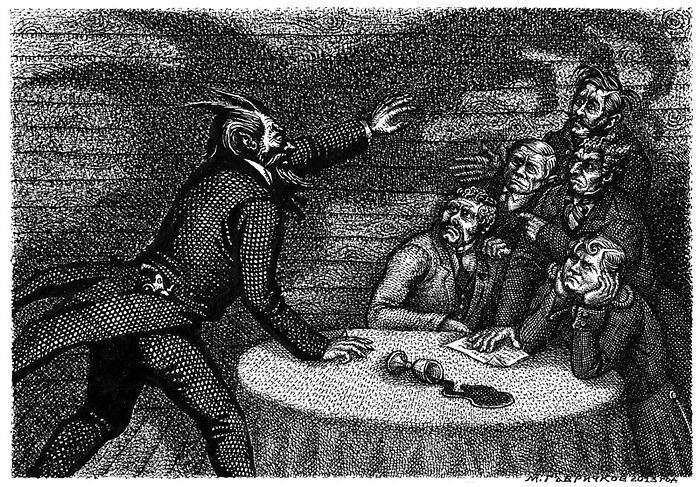

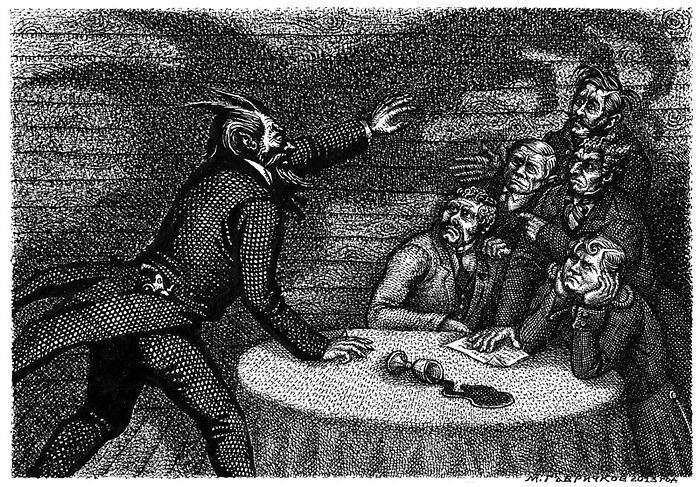

Illustration to Demons by M. Gavrichkov, pen and ink. Photo: fedordostoevsky.ru

Illustration to Demons by M. Gavrichkov, pen and ink. Photo: fedordostoevsky.ru

Shatov is disgusted with the revolutionary “five” that has been commandeered by Verkhovensky Jr., and he becomes a morose loner. But the more we get to know him the more we see that he is a deep and noble soul, who has returned to his Christian roots. He is a defender of the downtrodden; and when his “emancipated” wife shows up at his poor home, he receives her lovingly and chastely, ready to start a new, wholesome life with her.

His sister, Dasha, also stumbles in that she is ready to do anything for the profligate Stravrogin because she is hopelessly in love with him. Her love is self-sacrificing, expressed in a readiness to forever serve a man whom she knows is incapable of loving her back.

But here we see a higher level in the ongoing theme of “fatherhood”. While Stravrogin makes nervous attempts to return to a “father”—he even visits the holy Bishop Tikhon to confess a grave sin—the demons in him always get the upper hand. Whereas although Dasha and Ivan Shatov are cut off in a sense from their natural father, they are able to return to the embrace of their Heavenly Father, and their earthly Fatherland. They are wounded, but capable of becoming whole.

More tragic is Elizaveta Nicholaevna Tushina (Liza), the daughter of Varvara Petrovna’s childhood friend, Praskovia Ivanovna Drozdova. Liza also lost her father in childhood, and also received the tutelage of Stepan Verkhovensky. She is lively, attractive, and intelligent, but capricious, and also fatally drawn to the dangerous Stravrogin like a moth to the flame. He ultimately destroys her—almost against his own will, urged on by the devilish Peter Verkhovensky. She is a good soul, with natural religious piety. Her distant relative Maurice Drozdov loves her tenderly, chastely, and selflessly. That such a man would love her is already an indication of her goodness.

It is interesting that the most noble, religious, wholesome, and self-sacrificing person in the whole novel is also possibly the only character coming from a normal family. His father was well known, upright and respected. Maurice, incidentally, is the only person that Peter Verkhovensky can’t manipulate. He has a firm understanding of right and wrong, and sees through all his evil machinations. Notable again is the surname, Drozdov. The holy hierarch Philaret (Drozdov), Metropolitan of Moscow, was an important figure in the Russian literary world. It was he who answered Pushkin in the lofty, impeccable verses entitled, “Remember Me, Who Have Forgotten Thee”. In one episode, Maurice also very symbolically knees before a holy man whom his companions, which included Liza, had come to visit out of idle curiosity. To everyone’s astonishment, the holy elder bows down before him. As the tragic story unfolds, it becomes clear that this was a prophecy concerning the good Maurice, about whose fate at the end is only known that he left that town. Does he leave the world and become a holy monk?

There is one more fatherless child who appears only at the ominous end—Erkel, a young ensign artilleryman. “Erkel was the sort of “little fool” who lacked the real sense that should rule a man’s head… He was fanatically and childishly devoted to the Movement—that is, essentially to Peter Verkhovensky… Carrying out orders was a vital need of Erkel’s shallow, unthinking nature, which longed instinctively to be subordinated to another’s will. Oh, it goes without saying, it could only be in the name of some ‘great, common cause’—but what cause made no difference.” Erkel looks up to Peter Verkhovensky as the father he never had, someone to tell him what to do and guide him to something worthwhile. But in fact, Peter is really more like one of our modern cult leaders, teenage idols, or Antifa-type gang leaders who only use such youthful “zeal without knowledge” to their own egotistical ends, than he is a true father replacement. Erkel will do anything to gain his approval, even murder. His fanatical devotion to Peter makes him ready even to go to prison rather than betray him, imagining himself to be a kind of martyr for the “cause”.

Dostoevsky’s Demons portrays many more important psychological types who all contribute to the birth and growth of a Movement, the stated goal of which is “systematically to undermine the foundations of the existing order, to bring about the disintegration of the social structure and the collapse of all moral values, which would cause general demoralization and confusion. Then the broken, decaying society, sick and in full ferment, cynical and godless, but thirsting for some guiding idea and for self-preservation, could be taken over when the banner of revolution was raised…” Most of those contributing to the movement don’t even realize that they are digging their own graves. One can’t help but recall the fate of the Russian intelligentsia who so blithely, simply to make themselves relevant in the academic world, conveyed their liberal ideas to the youth, who then bore that seed and produced a vast, satanic meatgrinder, even murdering the main father of the Russian land—the “Tsar Batiushka” as Russian folk used to call their “Little Father, the Tsar”. The elder liberals ultimately spawned the younger nihilists. These cultured surrogate fathers could only look in horror at their own creations before either escaping the country, or disappearing into the hopper themselves. But they had no authority to control them, and were no match for their infernal dedication.

Fatherlessness is a tragedy, and the cause of so many blighted lives. But the worst kind of fatherlessness is when people have lost their connection with God the Father. They become like the lost souls who follow the devil, symbolized in Demons by the younger Verkhovensky, into the abyss of lawlessness. Dostoevsky, however, showed by his own life that when one remembers God and seeks Him, he can be pulled out of that abyss—albeit not without profound suffering.

An advertisement for the 2014 film, Demons

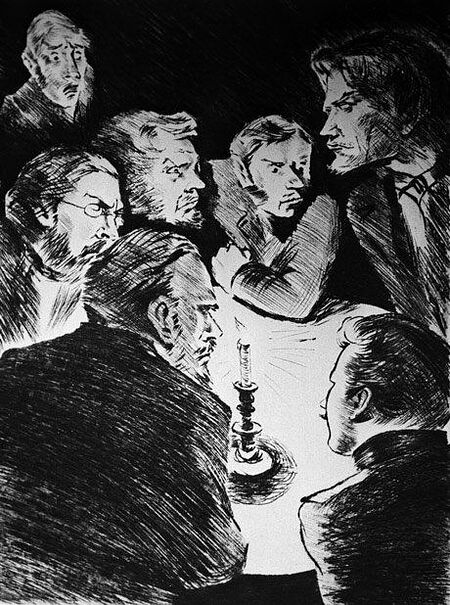

An advertisement for the 2014 film, Demons  Illustration to Feodor Dostoevsky’s novel, Demons. “The Five”, 1935.

Illustration to Feodor Dostoevsky’s novel, Demons. “The Five”, 1935.  Scene from the 2014 film, Demons.

Scene from the 2014 film, Demons.