St. Endelienda's Church in St. Endellion, Cornwall

St. Endelienda's Church in St. Endellion, CornwallThere is a humorous Cornish saying: “There are more saints in Cornwall than in Heaven.”

Among the host of saints who shone forth from the fifth to the seventh centuries in Cornwall to the far southwest of England, there were many women. We find holy missionaries, teachers, anchoresses, abbesses, nuns, righteous laywomen, martyrs, princesses and queens. Many of them were natives of Cornwall, but many came from Ireland and Wales where Orthodox Christianity flourished at that time. As is always the case with such saints, many of them were related, albeit the relation was not always necessary by blood—it was spiritual in many cases. These saints contributed much to the establishment of the Christian faith, world view and way of life in Cornwall for many centuries.

Though the history of Cornwall had periods of reversion to paganism, wars and invasions, the spirit and example of its early saints always nurtured, inspired and supported its inhabitants, and that is why they are still venerated today. The original Lives of nearly all the early Cornish saints were lost and the new accounts were written (often in a legendary form) by Roman Catholics after the Norman Conquest and contain only grains of truth. However, many traditions associated with the saints were passed down by pious folk from generation to generation and indeed there are some places in modern-day Cornwall where the memory of its ancient saints is still very much alive or being revived.

Almost all Cornish towns and villages are named in honor of a local saint; in some cases even rivers and bays are corruptions of local Celtic saints’ names, and nearly every settlement has a church or a chapel dedicated to its heavenly patron or patroness. In addition, there are dozens of pre-Norman holy wells, crosses and stones closely associated with saints. There are only a few shrines left, but the relics of saintly men and women may lie hidden under church floors, saved by pious people during the Reformation. Some pilgrims and tourists visiting Cornwall notice its atmosphere of holiness and feel the special presence of God in this early Christian (the first Christians may have appeared here in the first century) and mysterious land. Now let us recall several celebrated holy women of Cornwall.

Saint Breaga of Cornwall

Commemorated: May 1/14 and June 4/17

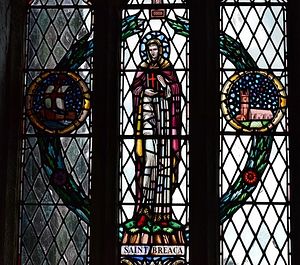

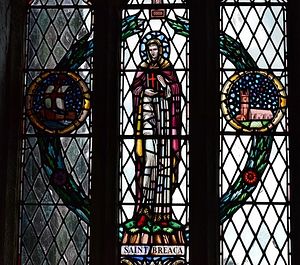

St. Breaca (Breaga) window inside Breage church, Cornwall (source - Michael Garlick from Geograph.org.uk)

St. Breaca (Breaga) window inside Breage church, Cornwall (source - Michael Garlick from Geograph.org.uk)Among them were Sts. Sinwin (Sithney, to whom a neighboring parish is dedicated), Germoe, Elwen, Crowan, and Helen, though the name forms change with time and vary in different locations. The missionaries first settled on the bank of the River Hayle, but some of them were soon murdered by the cruel ruler Tewdwr Mawr. However, we know that St. Breaga survived, arrived first in Pencair, then in Trenwith and Talmeneth, where she built churches. There is evidence that the holy woman travelled all over Cornwall and her missionary endeavors were successful despite the fierce pagan opposition in some districts. Some traditions claim that Breaga lived as an anchoress in Penrith for many years and that she was martyred by pagans (the latter is not supported by modern researchers).

The main church she founded was in what is now the village of Breage close to the south Cornish coast, where the holy handmaiden of God reposed and was buried. Her earliest chapel was a tiny wooden oratory housing the altar by a preaching cross where converts gathered for worship in the open air. That chapel was later replaced with a stone church. St. Breaga was held in great veneration after her death for many centuries, and her relics were famous for working miracles. In the Middle Ages St. Breaga was venerated across Cornwall and Devon, including in the Diocese of Exeter, and an annual fair in honor of this saint was held at Breage on the third Monday of June.

St. Breaga's Church in Breage, Cornwall

St. Breaga's Church in Breage, Cornwall Frescoes inside St. Breaga's Church in Breage, Cornwall

Frescoes inside St. Breaga's Church in Breage, CornwallThe present St. Breaga’s Church in the village of Breage was built of granite in around 1170. The structure has some Norman as well as many fifteenth-century elements. It was enlarged afterwards, with aisles, transepts and chapels added. Inside it has preserved some striking wall paintings. The most famous of these is that of “Christ of the trades”, depicting the wounded and lacerated Savior, with a large number of medieval tools below Him. There are two explanations for this unusual scene. Firstly, it was a colorful warning to illiterate medieval people against working on Sundays. Secondly, it could be simply Christ’s blessing of the work of various tradesmen. Other frescoes depict early saints, such as St. Ambrose and St. Christopher. They were rediscovered “by accident” under layers of plaster in the 1950s. A modern stained glass window on the south wall of the chancel depicts St. Breaga, its saintly patron. Other than that almost no noteworthy windows survive. Another unique feature of St. Breage’s is its nineteenth-century reredos carved by Belgian craftsmen. The church was reopened in 1879 following a major repair of its chancel.

Celtic cross in the churchyard of Breage church, Cornwall

Celtic cross in the churchyard of Breage church, CornwallA Celtic cross stands in the churchyard of Breage church next to the south porch. Interestingly, it is made of sandstone that cannot be found anywhere in the region. Perhaps it was purposely transported from somewhere to commemorate the saint or even mark her grave. The churchyard is circular in shape clearly indicating an early Celtic (and probably monastic) foundation. The village lies a few miles from the town of Helston which is famous among tourists for its custom of the “Furry Dance”.

Saint Endelienda of Cornwall

Commemorated: April 29/May 12

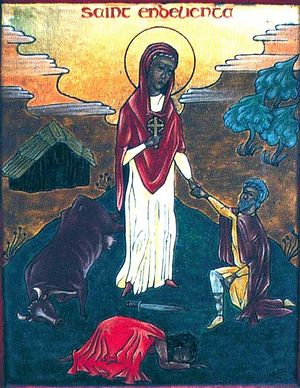

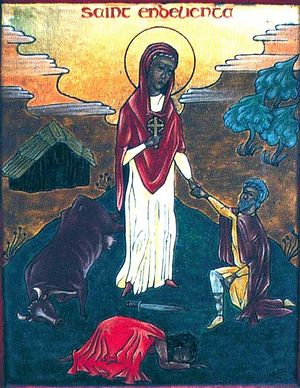

An icon of St. Endelienda

An icon of St. EndeliendaAccording to a popular tradition, St. Endelienda had a cow that provided her with milk every day for subsistence for many years. One day a local landlord, who was annoyed because the cow often strayed onto his grounds, in his fury killed the animal. The ruler executed the lord for this evil deed. The holy maiden could not tolerate this act of cruelty and began to pray hard to God. The Lord answered the intercessions of the venerable virgin and both the landlord and the cow were restored to life. It was said that grass in that area was greener than usual afterwards.

St. Endelienda predicted the day of her death. Shortly before her repose—according to tradition she was slain by pirates—the saint received communion for the last time. Before she died, Endelienda had gathered her disciples and gave them her final instructions. Notably, she ordered that after her death her body be laid on a cart yoked by two unguided calves. She told them to let these calves walk wherever they wished, for it would be the will of God. The calves pulled the cart and stopped at the top of a small hill in an idyllic spot. Now this village is called St. Endellion after her. There her relics were enshrined in a church which subsequently became collegiate. Large pilgrimages to St. Endelienda’s shrine at St. Endellion and to the site of her hermitage at Trentinney continued until the Reformation.

The village of St. Endellion lies in North Cornwall near the more famous picturesque village of Port Isaac on the coast. Its large parish church is still dedicated to St. Endelienda and commemorates her memory. It is built of granite moor stone in the Gothic Perpendicular style and dates back to the fifteenth century. This church is unique as it still holds a part of this saint’s shrine with her banner and an Orthodox icon of the saint (by John Colleman), depicting scenes from her Life and standing above it with candles lit alongside. It is a hard black stone altar which once served as the base of her main reliquary, her relics rested in a metal casket above it. The reliquary would be taken and carried in processions on her feast-day before the Reformation.

St. Endelienda's shrine base at St. Endellion church, Cornwall (source - Pinterest.co.uk)

St. Endelienda's shrine base at St. Endellion church, Cornwall (source - Pinterest.co.uk)Under Henry VIII the main shrine was destroyed, and if relics still survive, they lie concealed somewhere under the church floor. The shrine altar is in perfect condition however, and in the nineteenth century it was moved from the sanctuary to the south chapel. This holy object still contains all of its medieval consecration crosses and has eight niches all way round, which are now empty. The church font is Norman, and fine examples of wooden and stone carvings of different periods can be found within the church. The church tower is tall with three stages, and in former times it was used as a landmark for sailors navigating the north Cornish coastline. The church retains its collegiate status with clerical and lay prebendaries appointed for it (though their role is now ceremonial).

St. Endelienda’s Church in St. Endelion was loved by the English poet laureate John Betjeman (1906-1984), who is buried at St. Enodoc's Church in Cornwall. Famous for his self-deprecating, witty and gently satiric poetry, Betjeman, who loved English antiquity, the world of the English province and its ancient churches (he even compiled a guide to English parish churches), was a real phenomenon in English poetry in past decades, and he is commemorated on a plaque with an angel above him in St. Endellion’s chancel. Betjeman used to say that this church gives the impression that it goes on praying day and night, whether there are people inside it or not. “St. Endellion! St. Endellion! The name is like a peal of bells!” he once wrote. There are two holy wells in the vicinity of the village, and they bear the name of St. Endelienda who used their waters during her lifetime.

The village is also famous for its annual music festivals, bell-ringing traditions, and for its connection with Nicholas Roscarrock (1548-1634), a writer and antiquarian who studied the Lives of a great many early English saints and collected traditions about no fewer than 100 saints of Devon and Cornwall.

In 2010 the former UK Prime Minister David Cameron gave his and his wife Samantha’s daughter the name “Florence Rose Endellion” after Samantha had given birth nearby during their holiday. St. Endelienda is depicted with her symbols—the palm of martyrs, a cow and a well—on a bead of the unique sixteenth-century Longdale Rosary of gold and enamel, kept in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Saint Morwenna of Cornwall

Commemorated July 5/18

One of the most illustrious female saints of Cornwall is especially venerated in Morwenstow—the northernmost parish of Cornwall just beyond the Devon-Cornish border near the town of Bude. It stands on the rocky Atlantic coast with its frequent storms, and its name means “holy place of Morwenna”. We know little reliable information on St. Morwenna, who was born in the second half of the fifth century and died at the very beginning of the sixth century. Her earliest Life was lost, but she is mentioned in the twelfth-century Life of St. Nectan. According to tradition, she was one of the twelve holy daughters of the above mentioned King Brychan of Brecknock in Wales. She was born either in South Wales or Cornwall where her family had moved by the time of her birth. The name “Morwenna” most probably means “sea virgin”. The saint may have obtained a brilliant education in Ireland from where she returned to Cornwall as a missionary.

St. Morwenna's well in Morwenstow, Cornwall (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Morwenstow parish)

St. Morwenna's well in Morwenstow, Cornwall (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Morwenstow parish)The saint may have enlightened a large part of north Cornwall, but what we do know for certain is that she lived as an anchoress at Hennacliff (the name means “the raven’s crag”) by the sea, on a bluff on the edge of the precipice. This place was later named Morwenstow after her. St. Morwenna was famous for the many miracles that she performed. Where the waves are very high and the Welsh shore can be seen on clear days, St. Morwenna built a tiny cell for herself and a stone church for the local inhabitants with her own hands. The holy anchoress would carry heavy boulders from the coast up to the top of the cliff on her head. A miraculous holy well gushed forth from a boulder not far from the church through St. Morwenna’s prayers. The legend says that “when the church was being built, St. Morwenna was carrying a stone on her head up from beneath the cliff. When she put it down to rest and refresh, St. Morwenna’s well sprang up; when she finally dropped it again, in the place she wanted, the church was built there, although the first choice for its site was elsewhere.” Before St. Morwenna died, her brother St. Nectan visited her for the last time to give her communion. The saint asked him to lift her head onto his arm so that she could gaze across the Atlantic at her native Wales in the distance for the last time.

St. Marwenne's Church in Marhamchurch, Cornwall

St. Marwenne's Church in Marhamchurch, CornwallSt. Morwenna has been venerated in Morwenstow as well as other sites in Cornwall. Thus, the neighboring village of Marhamchurch is probably associated with her, though a number of modern researchers believe that this village is named after St. Marwenne—our saint’s holy sister of whom nothing is known. The fourteenth-century church at Marhamchurch is dedicated to her. The local parish on the Monday following August 12 organizes annual fetes with “reenactments” of St. Morwenna’s legends with parades (it is known that Morwenna was often accompanied by male and female assistants) and some traditional Celtic elements, with the crowning of “the Revel Queen” as its culmination. St. Morwenna is also the heavenly patroness of Lamorran in Cornwall, where the thirteenth-century church bears her name.

Exterior of the Morwenstow church, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)

Exterior of the Morwenstow church, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow) A wall painting of St. Morwenna praying over a monk inside Morwenstow church, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)

A wall painting of St. Morwenna praying over a monk inside Morwenstow church, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)Morwenstow, which is visited by Orthodox pilgrims, has a beautiful Norman parish church dedicated to St. John the Baptist and St. Morwenna. The first church on this site was Celtic and erected by Morwenna herself, and the current church has Norman and later elements. Its only Saxon feature is its fine tenth-century baptismal font. The church is beautiful, warm and welcoming inside. The relics of St. Morwenna are believed to rest somewhere under the church floor to this day, though their exact location is unknown. The people living here and pilgrims visiting this church note its special atmosphere of holiness, as if St. Morwenna were still alive here. An ancient faded wall-painting (fresco) on the north wall of the chancel is thought to depict its founding saint, Morwenna, praying for a priest (or a monk) presiding at the altar.

A stained glass depicting St. Morwenna in Morwenstow church, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)

A stained glass depicting St. Morwenna in Morwenstow church, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)There is an ancient holy well dedicated to St. John the Baptist just outside the churchyard of Morwenstow church (now on the grounds of a private house)—one of just a handful of working baptismal wells dedicated in Britain to this saint. The well-house is locked most of the time, though its water is still actively used for baptisms. The current font was certainly used for outdoor baptisms along with St. John’s well water in olden times. The former holy well of St. Morwenna still exists, though it looks abandoned, overgrown and difficult of access. It is on Vicarage Cliffs a mile away from the village on the cliff slope overlooking the ocean. Now it is sadly dry, but it is the remainder of the very well (mentioned above) that St. Morwenna founded herself while having a rest.

The Celtic cross head in the churchyard of Morwenstow church, Cornwall (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Morwenstow parish)

The Celtic cross head in the churchyard of Morwenstow church, Cornwall (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Morwenstow parish)There is a later Celtic cross head on the churchyard, although it is not associated with our saint and was originally used as a way-marker. In recent years there have been attempts to revive the veneration of Morwenna in Morwenstow. As for St. John the Baptist, there is an annual local patronal festival in his honor, which is attended by the school and many believers.

St. John's well at Morwenstow, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)

St. John's well at Morwenstow, Cornwall (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)It is said that this saint has appeared to other believers inside this church too. It is worth mentioning that Hawker’s life was not idyllic; rather it was full of stress. Apart from church ministry Hawker was determined to bury all shipwrecked sailors in the churchyard rather than on the beach where they were washed up or even left unburied (and there were so many such tragic incidents over the years of his ministry). The pastor, of course, compassionately prayed for their souls. The white-painted figure of one such ship, The Caledonia, is mounted in the church’s north nave aisle. All but one of its 10 sailors sadly drowned. And Hawker restored life in the Morwenstow parish, where before his arrival there had been desolation and a lot of smugglers.

Morwenstow church is decorated for the Harvest Festival (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)

Morwenstow church is decorated for the Harvest Festival (photo provided by the assistant curate of Morwenstow)Remarkably, it was thanks to Robert Stephen Hawker that the Harvest Festival was revived in English churches. He even wanted to revive the ancient (early English) service of harvest-day, the “Lammas-service”, but since it falls on August 1 according to the new calendar it would have been too early for the first crops. Thus, he invited his congregation to the church on the first Sunday of October, 1843, to give thanks to God for their bountiful harvest, realizing that the period when the crops were just gathered would be more convenient and practical. The idea was soon welcomed by other clergy, and now the Church of England has a fixed celebration for the Harvest Festival in its calendar; the Morwenstow parish was the first to celebrate it under Hawker. Though this priest and poet was not officially Orthodox, his soul and worldview were clearly orthodox. Hawker named one of his three daughters Morwenna after his favorite saint. He is buried and commemorated at the church, and what is known as “Hawker’s hut” stands on the way towards the cliffs from the church, now under the care of National Trust. Girls in Cornwall and Devon are baptized with the name “Morwenna” and some similar forms to this day.

Front door to Hawker's hut in Morwenstow, Cornwall (kindly provided by churchwarden of Morwenstow parish)

Front door to Hawker's hut in Morwenstow, Cornwall (kindly provided by churchwarden of Morwenstow parish) A view within Hawker's hut in Morwenstow, Cornwall (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Morwenstow parish)

A view within Hawker's hut in Morwenstow, Cornwall (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Morwenstow parish)Several years ago, Mrs. Maureen Wilson, who studied traditions associated with St. Morwenna, local history, customs, archeology and folklore for seven years, wrote a booklet entitled Unveiling Morwenna, based on “good circumstantial evidence” rather than actual facts. In the course of her research the author discovered that life in the fifth and sixth century Celtic Church was far from primitive; in fact it was much more organized and visionary than she believes the Church of England is today. The author suggests that Brychan was a charismatic religious figure of Romano-British learning rather than a king (the Celts referred to any figure of great importance as “royal”) and that the twenty-four children of King Brychan are not to be taken literally; rather, they were his purposefully-chosen twelve male and twelve female disciples.

A man of great wisdom, intelligence and insight, Brychan founded several “colleges” across his kingdom to train all of them and then sent them out for missionary endeavors to different lands. A saint himself, Brychan had several “cells” and “sketes” for retreat too. One of his spiritual children was St. Morwenna. The author goes on to suggest that on her arrival to Cornwall Morwenna set up a large-scale missionary and educational work, establishing several centers, schools, farms, having men, women and children among her disciples whom she also trained as missionaries. She suggests that the saint travelled energetically, excelled in crafts, agriculture, medicine (she along with other female saints often brought medicinal herbs to Cornwall with them, which is why local traditions claim that they “sailed to Dumnonia on a leaf”), and was very close to common people, helping them in everyday needs and labors. According to Mrs. Wilson:

1. Morwenstow was the probable farmstead where food for Morwenna’s missionary work was produced. (“stow” can also mean “subsidiary holding”).

It was a place she loved, and where she chose to die ... so her bones might well be here!

2. Kilkhampton was the most likely place for the saint’s mission school or college. (Kil means ”church cell”.) This village has quite a significant origin and is also accessible for students, (St. Morwenna is known as a “teacher saint”), and so this is a real possibility.

3. Marhamchurch was where St. Morwenna had her “retreat”, or hermitage. Some have argued that the saint of this village was different, and called St. Marwenne, but Mrs. Wilson’s research points to the fact they were one and the same person. (Spellings alter over 1,500 years). Nectan also had a hermitage, further along the coast from his base in Hartland.

4. Evidence shows one of St. Morwenna’s missionary journeys, away from her base, was to Morwellham Quay, in the south of the West Country peninsula.

5. Killock Farm near Kilkhampton was most probably the site of a small satellite station servicing St. Morwenna’s main mission. (Killock = “church/cell”.). Kilkhampton has a “Lady Well” and Killock has “St. Peter’s well”, both may have been associated with Morwenna.

6. Morwenna was not a pioneering missionary in Cornwall. By that time the seeds of the faith of Christ were being overshadowed by paganism in the period of social chaos, so Morwenna’s calling was to strengthen Christianity as a durable faith for generations to come. And indeed she inspired and influenced a substantial community. The Dictionary of National Biography for 1894 contains the names of several notable people with the surnames “Morwen”, “Morwyn” and similar forms, denoting that these families were once associated with communities founded by Morwenna. Many communities, even tiny and isolated ones, in north Cornwall, still hold Morwenna in great respect. Isn’t this the fruit of her tireless labors to enlighten, educate and take care of the inhabitants of this whole region?

(This information was received from the author of Unveiling Morwenna by correspondence).

We conclude Part 1 on women saints of Cornwall with this poem by R. S. Hawker:

MORWENNAE STATIO

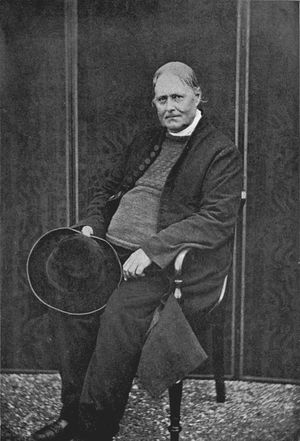

Robert Stephen Hawker

Robert Stephen Hawker

Wherein this weary heart hath rest:

What years the birds of God have found

Along thy walls their sacred nest!The storm—the blast—the tempest shock,

Have beat upon these walls in vain;

She stands—a daughter of the rock—

The changeless God’s eternal fane.

Firm was their faith, the ancient bands,

The wise of heart in wood and stone;

Who reared, with stern and trusting hands,

These dark grey towers of days unknown:

They fill’d these aisles with many a thought,

They bade each nook some truth reveal:

The pillar’d arch its legends brought,

A doctrine came with roof and wall.

Huge, mighty, massive, hard, and strong,

Were the choice stones they lifted then:

The vision of their hope was long,

They knew their God those faithful men.

They pitched no tent for change or death,

No home to last man’s shadowy day;

There! there! the everlasting breath,

Would breathe whole centuries away.

See now along that pillar’d aisle,

The graven arches, firm and fair:

They bend their shoulders to the toil,

And lift the hollow roof in air.

A sign! beneath the ship we stand,

The inverted vessel’s arching side;

Forsaken—when the fisher-band

Went forth to sweep a mightier tide.

Pace we the ground! our footsteps tread

A cross—the builder’s holiest form:

That awful couch, where once was shed

The blood, with man’s forgiveness warm.

And here, just where His mighty breast

Throb’d the last agony away,

They bade the voice of worship rest,

And white-robed Levites pause and pray.

Mark! the rich rose of Sharon’s bowers

Curves in the paten’s mystic mould:

The lily, lady of the flowers,

Her shape must yonder chalice hold.

Types of the Mother and the Son,

The twain in this dim chapel stand:

The badge of Norman banners, one

And one a crest of English land.

How all things glow with life and thought,

Where’er our faithful fathers trod!

The very ground with speech is fraught,

The air is eloquent of God.

In vain would doubt or mockery hide

The buried echoes of the past;

A voice of strength, a voice of pride,

Here dwells amid the storm and blast.

Still points the tower and pleads the bell;

The solemn arches breathe in stone;

Window and wall have lips to tell

The mighty faith of days unknown.

Yea! flood and breeze, and battle shock

Shall beat upon this church in vain:

She stands, a daughter of the rock,

The changeless God’s eternal fane.

(From Cornish Ballads and Other Poems, by R. S. Hawker, ed. by C. E, Byles, p. 49. This poem was first published in Ecclesia, 1840).

Holy Mothers Breaga, Endelienda and Morwenna, pray to God for us!