(

JTA) — On a Friday early in the coronavirus crisis, isolated in my apartment and facing the first of what would be many weekends with only Netflix for companionship, I came across a live Facebook video of Rabbi Zsolt Balla praying alone from the pulpit of his synagogue in Leipzig, Germany.

One of the first ordainees of the reconstituted Hildesheimer rabbinical school in Berlin, Balla settled in Leipzig with his wife in 2010 and began slowly rebuilding a Jewish community rejuvenated by the arrival of thousands of Russian Jews. Balla had even managed to sustain a daily prayer service before the coronavirus shuttered the country’s synagogues. Now here he was, praying alone into a computer, the rows of empty pews visible over his shoulder. It broke me to watch.

As the weeks unfolded, Balla would occasionally pop up in my feed. I’d click through and spend a few minutes watching him lead the prayers, his booming baritone echoing through the empty sanctuary behind him. Sometimes it was a weekday morning and he would be wearing his tefillin. More often it was Friday night, and he would chant the psalms welcoming the Sabbath in his pitch-perfect cantorial inflection. Unlike Zoom services with their sea of disembodied heads, Balla was streaming via Facebook — alone in a room, no virtual congregation surrounding him. I found it stark and poignant, even beautiful in its own way. And I wasn’t the only one.

“Dear Zsolt,” a Facebook commenter wrote. “I am not even jewish, and I do not really understand what you are talking about — yet somehow I managed to watch you and listen to you on a regular basis … It helps me somehow to end the day and to calm down … I do not know why this is … but I hope you don’t mind …”

In those early weeks, as the depth of the pandemic (and its staying power) was just beginning to sink in, I would regularly catch a few minutes of Balla doing his thing and acutely feel all that was being lost — not just to the Jewish community but to the world. All the lives on pause, the jobs lost, the scared and isolated people locked away in their homes staring into those hopeless little screens. The whole lot of human suffering seemed to echo in the sound of Balla’s prayers.

But as time went on, that faded. Humans adapt quickly, and what had once seemed unfathomably painful became just part of the furniture. Balla would appear in my feed, I would click through dutifully, but I was increasingly unmoved. What had seemed just weeks before like a potent symbol of these terrible times came to feel like just how it is now. People pray on Facebook in empty rooms in Germany.

Balla himself is a living symbol of the rebirth of Jewish life in that part of the world. Born in Budapest in 1979, he learned only as a child of 9 that he was Jewish. In 1991, the year after Hungary held its first free election following the fall of communism, Balla began attending a Jewish school in his hometown funded by the American cosmetics magnate and philanthropist Ronald Lauder.

Lauder was beginning to sink many millions into his quest to rehabilitate Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe, and Balla was both an early beneficiary of his largesse and a poster child for its impact. He went on to become a counselor at Camp Szarvas, a Jewish summer camp in Hungary funded by Lauder and the JDC humanitarian group, and after finishing his master’s degree in engineering and management studied at Lauder Yeshurun, the Jewish studies program in Berlin for young Jews with little background in Judaic studies.

“That was the first time I ever encountered successful young and normal Orthodox youth, which was an incredible experience,” Balla told me when we spoke in 2018. “In Hungary, I always had the impression of living up totally to the standards of Orthodox Judaism and at the same time being normal — it’s a contradiction. In Berlin, at the age of 23, I encountered that this was not the case.”

Balla wound up staying for three years, then spending another one in Israel. Upon his return, he began rabbinical studies, becoming one of the first two graduates of the Rabbinerseminar zu Berlin in 2009. The following year, he and his wife, the child of a secular Russian family who had come to Germany after the fall of communism, settled in Leipzig.

For Balla, it was less a job than a calling. He saw a reflection of himself in the Russian kids who had come of age under a repressive regime, barely aware that they were Jewish and understanding little of what that even meant. With hardly any locally grown rabbis to serve them, Balla felt a sense of duty to ensure they didn’t wait until their 20s to find out.

“It’s very important that we do not look at ourselves as people who got a job,” Balla said. “That’s not what we are here for. We are part of this community. I’m one of them. I happen to be the rabbi, but I’m one of them.”

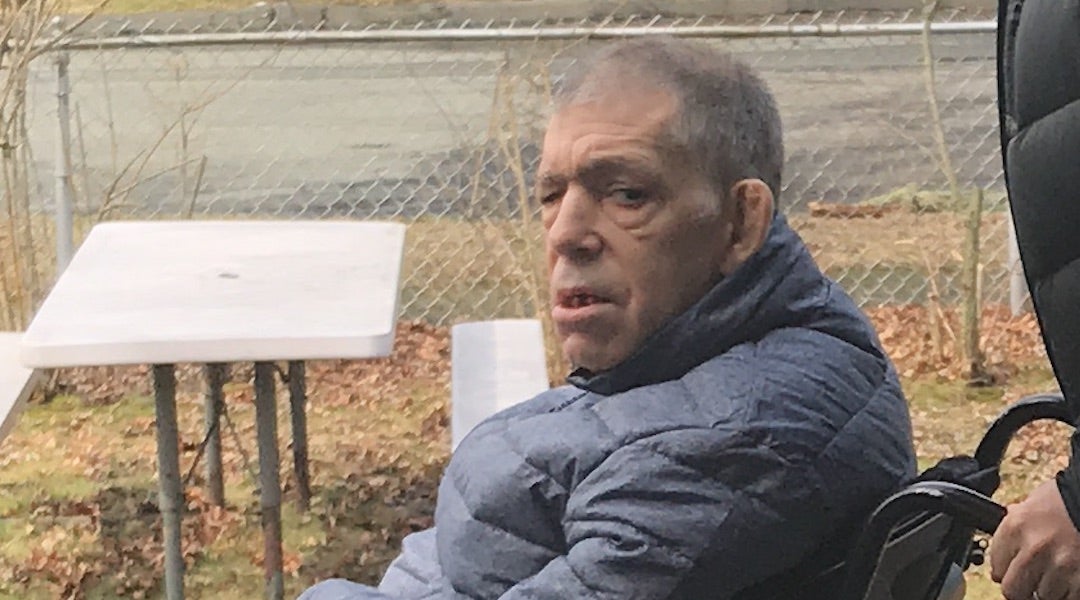

On Friday, when Balla popped up in my feed, he was wearing a face mask. I had never seen him do that before, and my first thought was that something terrible had happened. But as I looked closer, I understood: There were other people with him in shul. Only a handful were visible in the frame, and they were masked as well and sitting well apart from each other. Like so many others around the world, the Leipzig synagogue was taking its first tentative steps back toward normalcy.

I turned up the volume, but there wasn’t much to hear. Where Balla had sung all the words of the prayers aloud earlier in the pandemic, with a crowd on hand he was now saying most of the prayers quietly to limit the possibility of infection.

That particular shift was a hard one for Balla, who happens to lead an institute in Germany that trains Jewish prayer leaders. Singing has always been the part of prayer that most spoke to him, which is apparent to anyone who watches him lead services. Even as normalcy begins to draw tantalizingly near again, it’s obvious it won’t come immediately — and will look different when it finally does.

Balla is trying to see that as an opportunity. Having seen the reception of his livestreams across the world, he plans to continue them even once regular synagogue services are possible again.

It’s only a superficial change perhaps, but indicative of something deeper. When I started watching him back in March, my sense — or perhaps hope — was that the coronavirus was just a speed bump. We’d hunker down for a time, the storm would pass and we’d continue on our way. But increasingly it’s looking more like a fork. Like the mask that suddenly appeared on Balla’s face last week, that’s likely to be jarring for many of us — at least initially. But Balla wants to see it as an opportunity.

“You have to reboot, you have to rethink,” Balla said when we spoke this week. “I have always believed that one of the most important things that moves people is communal singing. In the local synagogues of my youth, it was mainly one guy in front giving a concert. This has never spoken to me. It’s like God is now saying, you think this was your value? Think again. It’s like a slap in the face.”

He continued: “I think this whole thing — I don’t feel like whatever we did was in vain. I feel like it’s a great opportunity to rethink what’s important for us. Where do you think as a Jewish community you’re going? I don’t have all the answers, but I think it’s a great time to contemplate these matters.”