LOCAL SAINTS OF NORTHERN ENGLAND: ALKELDA, EVERILDA, HERBERT AND GODRIC

St. Alkelda_s Church in Giggleswick, N. Yorkshire (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

St. Alkelda_s Church in Giggleswick, N. Yorkshire (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

In the “Age of the Saints” England produced a number of God-pleasers who have been venerated nationally, such as Sts. Alban of Verulamium, Augustine of Canterbury, Chad of Lichfield, Edmund of East Anglia, Etheldreda of Ely, Guthlac of Crowland, Swithin of Winchester, with churches dedicated to them in different counties. There were also quite a few saints who were well-known and venerated only in a particular region or regions. For example, the veneration of Sts. Birinus and Aldhelm was limited to the kingdom of Wessex, the veneration of St. Felix of Dunwich was concentrated in East Anglia, the veneration of St. Rumwold—in Mercia, of St. Mildred—in Kent. Lastly, there were numerous locally venerated saints whose church dedications and popularity were limited to relatively small areas, often one town or village. Among these were quite a few interesting and great saints, whose memory should not sink into oblivion.

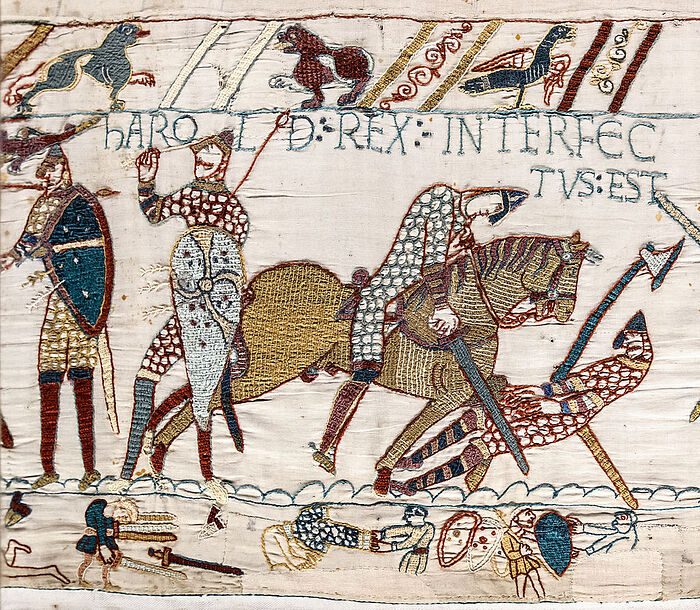

The reasons for local veneration of such saints vary: in some cases they lived in one place without moving or travelling and little information about them is known; in other cases their fame was eclipsed by the popularity of another saint, or their wide veneration was prevented by historical processes, especially attacks by pagan Scandinavians or the Norman Conquest of England, after which there were attempts to erase the memory of the pre-Norman saints. In a series of articles we will try to acquaint readers with some of these saints. This overview will not include all the locally venerated saints of Britain, but only the ones whose stories are the most interesting, or whose holy places are of significance today. The saints about whom we know next to nothing will be briefly mentioned at the end of each article.

In the first millennium A.D. what is now northern England was dominated by the large Anglian kingdom of Northumbria, an amalgamation of the kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira. There were also small Celtic kingdoms, especially in what is now Cumbria, which was quite isolated and inhabited by Britons, forming the kingdom of Rheged, and, after two centuries of Northumbrian dominance, it became part of the Celtic kingdom of Strathclyde for a time. Not only Angles, but also the Norse and (in the western shores) the Irish settled in the north. The north of England was a beacon of Christianity in the “dark ages” not only in England, but at a European level. This remarkable civilization continued from the conversion of King Edwin in 627 to the beginning of the Viking raids two centuries later. It was a successful blend of the so-called early English and Irish Orthodox traditions.

The great Celtic saints Kentigern Mungo, Ninian, and Patrick partly labored in the western part of the region. Northumbria produced such outstanding figures and ascetics as the Venerable Bede, Sts. Benedict of Wearmouth, Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, Hilda of Whitby, John of Beverley, and Wilfrid of York. Such masterpieces of Christian culture as the Lindisfarne Gospels were created here; such great missionaries as Sts. Aidan and Paulinus built churches, monasteries and erected crosses; such holy kings as Edwin and Oswald ruled this land. This landscape is still dominated by celebrated centres of Christianity—Beverley, Durham, Jarrow, Hexham, Lindisfarne, Ripon, Whitby and York. The natural landscapes are as stunning: from the Yorkshire Dales and the North York Moors to the Lake District, with marshes, moorlands, mountains, lakes, rivers, forests, valleys, wildlife, ancient walls and Roman-era structures, along with ruins of magnificent medieval abbeys. The region served as the literary inspiration for the Bronte sisters, James Herriott and many other authors. The most notable local saints of the English north are Alkelda, Everilda and Herbert. However, there is also a very interesting local figure named Godric, whom we shall consider below.

Martyr Alkelda (Alkeld, Athilda) of Middleham

Commemorated: March 27 / April 9 and November 5 / 19

St. Alkelda embroidered banner at church in Giggleswick, by Barbara Thornton (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

St. Alkelda embroidered banner at church in Giggleswick, by Barbara Thornton (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

Unfortunately, no early records of this saint survive. We can rely only on local oral tradition and later sources. St. Alkelda may have been a noble Northumbrian lady and virgin who lived in the late ninth or the tenth century who chose to lead the life of a nun or an anchoress, probably undertaking missionary work in what is now the Yorkshire Dales. She was strangled by some Danish women, receiving martyr’s crown. She was greatly venerated in what is now the small market town of Middleham and the village of Giggleswick, both in North Yorkshire and within the Yorkshire Dales, thirty-three miles apart. A number of local holy wells were associated with her, and their waters cured eye infections and other diseases. The Anglican church in Middleham is dedicated to Sts. Mary and Alkelda, and its Giggleswick counterpart—to St. Alkelda. In the Middle Ages St. Alkelda’s shrine with her relics was in Middleham church.

Stained glass depicting St. Alkelda_s martyrdom at the Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (provided by co-rector of the church in Middleham)

Stained glass depicting St. Alkelda_s martyrdom at the Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (provided by co-rector of the church in Middleham)

The relics survived the Reformation and were buried under the church floor. In 1878, during renovation work, the floor was opened and an ancient primitive stone coffin was uncovered beneath the southeast part of the nave. According to specialists of the time, inside it were the bones of a female, which with a high degree of certainty belonged to St. Alkelda; because according to tradition her coffin had been buried exactly in that place. The remains were reburied soon after their discovery and now this site is marked by a brass plaque on a pillar, bearing the inscription: “Near this pillar, on the spot indicated by tradition, were found, during the work of restoration, the remains of St. Alkelda, patron saint of this church, Anno Domini 1878. F. Barker, rector; T. E. Swale and S. Croft, churchwardens.” A fragment of an elaborate carved stone with an early English knotwork design set in the nave floor near the lectern could be a part of her pre-Norman shrine.

Stained glass depicting St. Alkelda_s ascension in the Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (provided by co-rector of the church in Middleham)

Stained glass depicting St. Alkelda_s ascension in the Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (provided by co-rector of the church in Middleham)

Over the past few years much effort has been put in by the congregations of both Middleham and Giggleswick to promote their patron-saint and revive her memory. St. Alkelda is celebrated in both parishes annually; there are many memorials in both churches dedicated to her. In 2019 a thirty-three-mile heritage pilgrimage path, St. Alkelda’s Way, was launched. It connects Middleham and Giggleswick, and is devoted to the memory of this saintly woman. Before the outbreak of the Covid epidemic, the first self-guided pilgrimage walks across this area were successful. It is a contemporary example of the revival by enthusiasts of the ancient veneration of a previously forgotten local saint. One of the inspirers and creators of this project is Mrs. Kathleen Kinder, a member of the Giggleswick parish, a researcher of early English and Irish holiness and historian, to whom we are indebted for most of the information on St. Alkelda in this article. The route passes through some of the most beautiful and varied scenery in the country, using the ancient paths that St. Alkelda may have trodden.

Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (photo by Philip Platt, Geograph.org.uk)

Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (photo by Philip Platt, Geograph.org.uk)

Middleham church has been of importance since the Middle Ages. The patent of Edward IV (1461—1483) survives which enabled his brother Richard Gloucester (the future Richard III) to set up the college of Middleham in honor of Christ, the Mother of God, and St. Alkelda, so the church had a collegiate status with its dean and canons till 1840. The young son of Richard III, Edward Middleham, Prince of Wales, was probably buried in this church in 1484. In 1559, the dean of Middleham left a piece of St. Alkelda’s head as a bequest in his will. The west window of the north aisle has a fifteenth-century roundel depicting St. Alkelda’s martyrdom at the hands of two vicious-looking Viking women. It was assembled out of some broken pieces. Two medallions set into stained glass in the vestry commemorate her martyrdom and ascension. There is a picture of St. Alkelda by the entrance to her grave.

At the back of the church there is a replica of the fifteenth-century Middleham Jewel, discovered in 1985 in a field by the local castle. The original is in the Yorkshire Museum, York. It is a personal diamond-shaped gold pendant with a sapphire with engravings of the Trinity on the front and the Nativity on the reverse; it was used as a reliquary. The Middleham church dates back to about 1280—1290, with some Norman elements. The fame of St. Alkelda was so great that in 1388 King Richard II granted Middleham the right to hold an annual fair on St. Alkelda’s feast. The fair was one of the largest in the area and lasted three days; it was discontinued in 1926. There was St. Alkelda’s well west of the Middleham church, which was believed to mark the saint’s site of martyrdom. Now it is dry, hidden in a stone wall—the underground water courses that supplied it have been diverted to build new houses. But at least until recently there was an old well chamber further downhill that was full of water.

Cross shaft in the churchyard of St. Alkelda_s Church in Giggleswick, N. Yorkshire (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)The building of St. Alkelda's Church in Giggleswick is late fifteenth century, though it has Norman work on some pillar bases. The earlier building was badly damaged or destroyed in a Scottish raid in 1319 (its early English foundations were found in the crypt). There is an early English cross shaft in the churchyard by a south door. St. Alkelda is commemorated in this church in a number of ways. In 2019 a new mysterious stained glass window featuring St. Alkelda being strangled while suspended over water was installed in the church. It was earlier discovered in the parish room in the form of beautiful separate panel pieces of an unknown provenance and has been since lovingly restored (the church had medieval windows smashed by Cromwellian soldiers; some pieces were picked up during the 1890-92 restoration, but their whereabouts is unknown).

Cross shaft in the churchyard of St. Alkelda_s Church in Giggleswick, N. Yorkshire (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)The building of St. Alkelda's Church in Giggleswick is late fifteenth century, though it has Norman work on some pillar bases. The earlier building was badly damaged or destroyed in a Scottish raid in 1319 (its early English foundations were found in the crypt). There is an early English cross shaft in the churchyard by a south door. St. Alkelda is commemorated in this church in a number of ways. In 2019 a new mysterious stained glass window featuring St. Alkelda being strangled while suspended over water was installed in the church. It was earlier discovered in the parish room in the form of beautiful separate panel pieces of an unknown provenance and has been since lovingly restored (the church had medieval windows smashed by Cromwellian soldiers; some pieces were picked up during the 1890-92 restoration, but their whereabouts is unknown).

Three St. Alkelda_s windows at the west end in St. Alkelda_s Church, Giggleswick - photo by Nigel Mussett (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

Three St. Alkelda_s windows at the west end in St. Alkelda_s Church, Giggleswick - photo by Nigel Mussett (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

There are three panels with images of scenes of St. Alkelda’s life in the west window of the church. The saint is represented in stained glass window in the Memorial (formerly Lady) Chapel. There is an embroidery-fabric collage banner of St. Alkelda, designed by the warden Barbara Thornton. The altar and its rails are of seventeenth century oak. The east window is beautiful and has scenes of the Lord's crucifixion and ascension. The Giggleswick churchwardens’ staff ends are decorated with a little figure of St. Alkelda.

St. Alkelda panel detail from the newly-discovered stained glass at church in Giggleswick (photo by Lightworks, kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

St. Alkelda panel detail from the newly-discovered stained glass at church in Giggleswick (photo by Lightworks, kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

St. Alkelda of Middleham window at RC church in Settle, N. Yorkshire (photo by Margaret Fox, kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

St. Alkelda of Middleham window at RC church in Settle, N. Yorkshire (photo by Margaret Fox, kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)

The first mention of St. Alkelda as the patroness of this church is in the late fourteenth century because of the general increased the veneration of the Mother of God and the saints following the Black Death, which was experienced nationwide. In Alkelda’s time, Giggleswick lay just within the boundaries of Northumbria and more remote from Christian influences. The saint might have undertaken hazardous journeys to this area to share her faith with its populace. In her time, the Yorkshire Dales, apart from separate villages with cultivated land, was a wilderness, a habitat for dangerous animals and a haven for outlaws. Even if there were no Danes, it would still have been dangerous. St. Alkelda was guided by burning love and courage.

The Bank Well at Giggleswick, N. Yorkshire (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)Of the ancient wells in Giggleswick, the best preserved is the Bank Well beside the old vicarage, which never dries up. It has existed since the Roman and pre-Roman eras and was formerly used in healing practices. The ancient Ebbing and Flowing Well, symbolically featured in a window of the Giggleswick Church, is outside the village, by a roadside, with the Giggleswick Scar, a local landmark, towering behind it. Lastly, St. Alkelda’s well was located on the Holywell Toft (hill) near the present school. Its waters were put underground during the rebuilding of the public school of Giggleswick (founded in 1499) in 1850. The headmaster’s house was built over the well, which emerges at the local conduit and still flows alongside the village main street. A number of early English crosses were found in the nearby caves, and an early English chapel has been dug out at Malham close by. We can only speculate if St. Alkelda was connected with these relics.

The Bank Well at Giggleswick, N. Yorkshire (kindly provided by Kathleen Kinder)Of the ancient wells in Giggleswick, the best preserved is the Bank Well beside the old vicarage, which never dries up. It has existed since the Roman and pre-Roman eras and was formerly used in healing practices. The ancient Ebbing and Flowing Well, symbolically featured in a window of the Giggleswick Church, is outside the village, by a roadside, with the Giggleswick Scar, a local landmark, towering behind it. Lastly, St. Alkelda’s well was located on the Holywell Toft (hill) near the present school. Its waters were put underground during the rebuilding of the public school of Giggleswick (founded in 1499) in 1850. The headmaster’s house was built over the well, which emerges at the local conduit and still flows alongside the village main street. A number of early English crosses were found in the nearby caves, and an early English chapel has been dug out at Malham close by. We can only speculate if St. Alkelda was connected with these relics.

Some contemporary historians question St. Alkelda’s existence and claim that her name is a corruption of “Halig-kelda”—the Anglo-Saxon-Norse for “holy well”. However, there is a strong oral tradition that this saint did exist, and the most eloquent witness is the rediscovery of her coffin with what are probably her relics. Some conjecture that “Alkelda” was not the saint’s given name, but perhaps her affectionate nickname, while her real name was forgotten. St. Alkelda might have been a missionary, administering to local inhabitants, arranging for their Baptisms, preaching and erecting crosses. There are tragic historical reasons why we know so little about this heroic virgin. The Danes attacked and destroyed York in c. 867 and swept across the Vale of York and the eastern Dales, burning and killing as they went. St. Alkelda was easily martyred by them. There was no one left to tell her story—the Danes were pagan and illiterate. (The above mentioned carved pattern on her tomb, based on a plait with a knot at the end, was not used by the carvers in stone until the end of the Northumbrian era, and that fits with what we know of the time of her death).

Early English knot pattern at the Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (provided by co-rector of the church in Middleham)

Early English knot pattern at the Church of Sts. Mary and Alkelda in Middleham, N. Yorkshire (provided by co-rector of the church in Middleham)

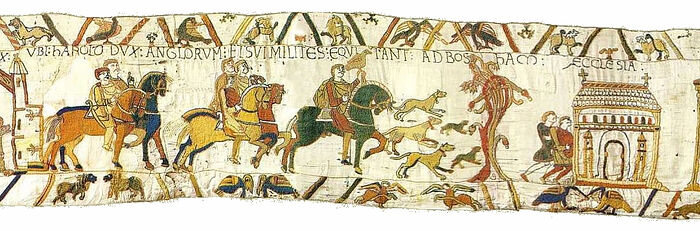

In the Domesday Book of 1087—the record of a survey of the land of England carried out by the commissioners of King William the Conqueror—Middleham was described as “waste” and Giggleswick as “waste implied”. The term refers to the terrible punishment known as “the harrying of the north” (1069-71) that William exacted on the rebellious people of the north; on their towns, villages, lands and crops. What he did was horrific, described as genocide, causing the deaths of over 100,000 people. He not only burnt crops, he salted the land rendering it infertile for years. The survivors starved or took to cannibalism. Middleham must have been a center of rebellion because two defensive motte and baileys were built within five miles of each other.

The Middleham one was built as William returned south. Middleham suffered more than Giggleswick, but this is why no churches were mentioned in the Domesday book—they would have been destroyed. But in Middleham, St. Alkelda's tomb was left behind and the Norman church was eventually built over it. The Normans brought the French language with them. Under them, French was the language of the court, while Latin became the scholarly and Church language. St. Alkelda’s feat was kept alive only in folk memory. It was not until the late fourteenth century, after the Scottish raids and the terrible plague, that inhabitants of Northumbria began to return to their English roots and write in English.

St. Alkelda is remembered in the town of Settle on the River Ribble at the edge of the Yorkshire Dales near Giggleswick—there she is depicted on stained glass in the Catholic church of Sts. Mary and Michael.

Venerable Everilda, abbess of Everingham

Commemorated: July 9/22

A side-chapel altar in the RC Church of Sts. Mary and Everilda in Everingham, East Riding of YorkshireThe only source for the life of St. Everilda (Everild, Everildis, Averil), who is venerated in two places in Yorkshire, is the late medieval York Breviary. She was probably a noble lady of the Kingdom of Wessex, converted and baptized by St. Birinus, the enlightener of the kingdom, in about 635. With his blessing, later the holy woman decided to leave behind all her worldly cares and took the veil in the north of England, where she travelled with two other maiden ascetics. She might have been tonsured by St. Wilfrid of York in a place called Bishop’s Farm, which is identified by most historians with the present-day village Everingham in the East Riding of Yorkshire (according to another version, her convent was elsewhere in Yorkshire and the village’s name means “place of Eofer’s people” after an individual named Eofer), which probably bears her name. St. Wilfrid may have granted her land; St. Everilda became the first abbess of the local convent and ruled it for many years, gathering a community of eighty nuns. The abbess served the Lord in purity, prayer and holiness, taking care of her sisters and setting for them the example of her life. St. Everilda reposed in the Lord in about 700 at a very advanced age, and pilgrims flocked to her relics after her death.

A side-chapel altar in the RC Church of Sts. Mary and Everilda in Everingham, East Riding of YorkshireThe only source for the life of St. Everilda (Everild, Everildis, Averil), who is venerated in two places in Yorkshire, is the late medieval York Breviary. She was probably a noble lady of the Kingdom of Wessex, converted and baptized by St. Birinus, the enlightener of the kingdom, in about 635. With his blessing, later the holy woman decided to leave behind all her worldly cares and took the veil in the north of England, where she travelled with two other maiden ascetics. She might have been tonsured by St. Wilfrid of York in a place called Bishop’s Farm, which is identified by most historians with the present-day village Everingham in the East Riding of Yorkshire (according to another version, her convent was elsewhere in Yorkshire and the village’s name means “place of Eofer’s people” after an individual named Eofer), which probably bears her name. St. Wilfrid may have granted her land; St. Everilda became the first abbess of the local convent and ruled it for many years, gathering a community of eighty nuns. The abbess served the Lord in purity, prayer and holiness, taking care of her sisters and setting for them the example of her life. St. Everilda reposed in the Lord in about 700 at a very advanced age, and pilgrims flocked to her relics after her death.

It is conjectured that St. Everilda was a relative of a princess of Wessex and attended the wedding of the holy King Oswald of Northumbria and Princess Cyneburh in 635. With her family being Christian by the 640s thanks to St. Birinus, St. Everilda may have travelled north to Northumbria on St. Oswald’s invitation to avoid a dynastic marriage and devote her life to the service of God. However, the circumstances of her move from Wessex to Northumbria are impossible to ascertain.

This is what the Catholic priest and hagiographer Alban Butler (1710—1773) wrote about St. Everilda: “She trained many nuns to the perfection of Divine love, the summit of Christian virtue, animating them with the true spirit of the Gospel, encouraged them in the faithful discharge of all the duties of their holy state, until she was called to God.” According to tradition, the saint blessed women and mothers of Everingham for all times—it was said that no woman died in childbirth in this village; this was true for many years and was testified about relatively recently! The name of St. Everilda can be found in the medieval calendars of York and Northumbria and in a couple of early martyrologies.

No traces of the saint’s convent survive in Everingham and its former location is uncertain. No church was mentioned in the village in the Domesday Book. The desolated state of the village at that time is obviously explained by William I’s harsh punitive campaign mentioned above. Today Everingham can boast of two churches that bear the name of St. Everilda. Firstly, the Anglican Church of St. Everilda, a small in size but active parish that celebrates its patron-saint every year on July 9, and holds a village fete to raise funds for the church on this day. The church was built in the thirteenth century, largely reconstructed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and reroofed in the nineteenth century. It was originally dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin, but by the nineteenth century it had been known as St. Everilda’s. Now it bears a double dedication. Secondly, there is a fine Catholic Church of Our Lady and St. Everilda, which was consecrated in the 1830s and at one time held Tridentine services.

The Anglican Church of St. Everilda in Everingham, East Riding of Yorkshire

The Anglican Church of St. Everilda in Everingham, East Riding of Yorkshire

The impressive church was built in the grounds of Everingham Hall soon after the Act of Emancipation of the Catholics as there had been many recusant Catholics in the area. Alas, the Catholic hierarchy stopped supporting this church in 2004, and it has been privately owned ever since. It is used for Christmas carol services and other occasional services jointly by local Anglicans and Catholics. This church was built in the Italianate style and is noted for its splendid Corinthian columns, apsidal altar, barrel-vault, organ, font, depictions of scenes from the life of Christ, and fine statues of the apostles, the Mother of God and St. Everilda. There used to be an ancient St. Everilda’s healing well near the Everingham church, which was blessed by St. Everilda herself. A nineteenth-century author wrote that the well sat 200 meters northeast of the Anglican church but was covered. Today, a stream may indicate the source of the original well.

St. Everilda_s Church in Nether Poppleton, North Yorkshire

St. Everilda_s Church in Nether Poppleton, North Yorkshire

St. Everilda is also remembered in the village of Nether Popleton (the name meaning “pebble farm”) by the River Ouse four miles from the city of York in North Yorkshire. It has an Anglican church dedicated to our saint, which was built in the eighth century but reconstructed in the middle ages. Some of its stained glass is medieval. It is situated some twenty miles northwest of its Everingham counterpart. Archeological excavations have found evidence of the presence of a monastic building in the village, making Poppleton a serious candidate for the location of St. Everilda’s convent.

Righteous Herbert of Derwentwater

Commemorated: March 20 / April 2

Sts. Cuthbert and Herbert (by Aidan Hart)The only author to mention this saint is St. Bede of Jarrow, who wrote about St. Herbert in his History of the English Church and People and his version of the Life of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne. St. Herbert (Herebert), an Anglian by birth, was a righteous priest and anchorite who lived on one of the seven islands on Derwentwater, a beautiful lake three miles long and one mile wide in the Lake District national park in Cumbria. This lake is a ten-minute walk south from the center of the picturesque market town of Keswick. St. Herbert was a disciple and close spiritual companion of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne in the second half of the seventh century. Let us cite St. Bede himself.

Sts. Cuthbert and Herbert (by Aidan Hart)The only author to mention this saint is St. Bede of Jarrow, who wrote about St. Herbert in his History of the English Church and People and his version of the Life of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne. St. Herbert (Herebert), an Anglian by birth, was a righteous priest and anchorite who lived on one of the seven islands on Derwentwater, a beautiful lake three miles long and one mile wide in the Lake District national park in Cumbria. This lake is a ten-minute walk south from the center of the picturesque market town of Keswick. St. Herbert was a disciple and close spiritual companion of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne in the second half of the seventh century. Let us cite St. Bede himself.

Chapter 28 of the Life of St. Cuthbert (translated from Latin by J. F. Webb, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, first printed in 1965):

“He (St. Cuthbert) was invited to Carlisle [now the county town of Cumbria.—Auth.] to ordain some deacons to the priesthood and to give the religious habit with his blessing to the queen. There was a holy priest called Hereberht, long bound to Cuthbert in spiritual friendship, living the hermit's life on an island in that great lake from which the River Derwent flows. He used to come to Cuthbert (to Lindisfarne) every year to take counsel about his eternal salvation. Hearing that he was staying at Carlisle, Hereberht came to him, seeking, as usual, to be fired with an ever-increasing love for the things of Heaven. While they were regaling each other with draughts of celestial wisdom Cuthbert said casually: ‘Remember, brother Hereberht, to ask me now whatever you need to ask. This is the last time we see each other with the eyes of the flesh, for the time is at hand when I must lay aside my earthly tabernacle; the time of my departure is nigh.’Hereberht flung himself at his feet and sobbed. ‘In the Lord's Name, do not leave me. Think of your friend and ask the Divine Mercy to grant that, as we have served Him together on earth, so we may journey forth together to see His glory in Heaven. I have always striven to follow your commands, and whenever ignorance or human frailty has led me astray I have always chastised myself as you judged fit.’

“The bishop prayed fervently and was given to know that his prayer was answered. ‘Rise up, brother; do not weep. Rejoice and be glad, for the Divine Mercy has granted our prayer.’

“This was borne out by the course of events. Hereberht departed, and they saw each other on earth no more, but their souls left their bodies at one and the same moment and were carried to the celestial kingdom by an angel, to be united with each other in the beatific vision. Hereberht's death was preceded by a long racking illness, inflicted perhaps by God in His mercy, to make sure that, if previously he had lagged behind Cuthbert in merit, he might now be made equal to his intercessor through suffering and so deserve to depart this life with him at the same time and be received into the same eternal bliss.”

Site of St. Herbert_s hermitage on St. Herbert_s Island, Derwentwater, Cumbria (photo by Antony McCann, Geograph.org.uk)

Site of St. Herbert_s hermitage on St. Herbert_s Island, Derwentwater, Cumbria (photo by Antony McCann, Geograph.org.uk)

Both Sts. Cuthbert and Herbert fell asleep in the Lord on March 20 / April 2, 687—Cuthbert on Inner Farne and Herbert on his isle. Although St. Herbert was venerated as a saint after his death and was mentioned in a number of early calendars (for example, in the Martyrology of Tallacht in Ireland), St. Cuthbert’s feast was by far much more popular than St. Herbert’s and the veneration of the latter has always been very local. Christians of the English county of Cumbria honor his memory to this day. The small island on which St. Herbert struggled in prayer, is called “St. Herbert’s Island” (or locally “Herbert Island”) after him. The island is the largest of its neighbors (covering over four acres) and sits in the middle of the lake. Presumably other Christian hermits lived in St. Herbert’s cell after him up to the Viking raids or even after the Norman Conquest, but we have no evidence to prove this. A hermitage stood on this site for some centuries. In 1374 Thomas Appleby, the Catholic Bishop of Carlisle, ordered local vicars to annually celebrate the Mass on St. Herbert’s Island on the saint’s feast-day and granted a forty-day indulgence to pilgrims who visited it. The Friars’ Crag on this isle is named after the medieval monks who sailed here.

After (or even before) the Reformation, the cell fell into disrepair and gradually into ruin. In the Middle Ages, Catholics may have built a chapel or chapels on the isle, but only minor remains survive. It is possible to hire a boat from Keswick to reach the isle, admiring the glorious scenery around. On the isle itself, one of the most idyllic hermitage settings in all England, there is an area of the remains of a few stone structures and some dark separate boulders. The most identifiable is a circular foundation of a building with traces of high solid walls, but all mostly buried. Though the site is marked on some maps as a summerhouse ruin, the antiquary and poet John Leland (c. 1503–1552; “the father of English local history”) described a chapel on the same spot. Modern pilgrim guide books say with a considerable degree of certainty that this structure is a remainder of St. Herbert’s hermitage or remnants of a later pilgrims’ chapel built in his memory.

Whatever the truth may be, Catholic as well as Orthodox pilgrimages from Keswick, the rest of Cumbria and beyond are organized to this isle every year, with open-air prayers and services.

Derwentwater, Cumbria

Derwentwater, Cumbria

The famous “romantic” poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850) dedicated one of his poems to the friendship between Sts. Cuthbert and Herbert and St. Herbert’s Isle:

For the Spot Where the Hermitage Stood On St. Herbert’s Island, Derwentwater

If thou in the dear love of some one Friend

Hast been so happy that thou know’st what thoughts

Will sometimes in the happiness of love

Make the heart sink, then wilt thou reverence

This quiet spot; and, Stranger! not unmoved

Wilt thou behold this shapeless heap of stones,

The desolate ruins of St. Herbert's Cell.

Here stood his threshold; here was spread the roof

That sheltered him, a self-secluded Man,

After long exercise in social cares

And offices humane, intent to adore

The Deity, with undistracted mind,

And meditate on everlasting things,

In utter solitude.—But he had left

A Fellow-labourer, whom the good Man loved

As his own soul. And, when with eye upraised

To heaven he knelt before the crucifix,

While o’er the lake the cataract of Lodore

Pealed to his orisons, and when he paced

Along the beach of this small isle and thought

Of his Companion, he would pray that both

(Now that their earthly duties were fulfilled)

Might die in the same moment. Nor in vain

So prayed he:—as our chronicles report,

Though here the Hermit numbered his last day

Far from St. Cuthbert his beloved Friend,

Those holy Men both died in the same hour.

Fans of Beatrix Potter (1866–1943) remember that she spent her holidays in the area in 1901, where she wrote her short story, “Squirrel Nutkin”, in which St. Herbert’s Island is featured as “Owl Island”; the author also painted this holy isle from both sides of the lake as her book illustration.

A number of modern Anglican and Catholic parishes in Cumbria and elsewhere are dedicated to St. Herbert. Let us mention St. Herbert’s churches in Braithwaite and Windermere; St. Herbert and St. Stephen’s Church in Carlisle; St. Herbert’s Church, Currock, Carlisle; St. Herbert’s Anglican School in Keswick (all in Cumbria); St. Herbert’s Church in Darlington, co. Durham; St. Herbert’s Church in Chadderton, Greater Manchester; St. Herbert’s RC School in Chadderton, Oldham. There is also a Greek Orthodox parish of Sts. Bega, Mungo and Herbert in Keswick, Cumbria.

***

Other Local Saints of the North of England:

—St. Echa of Crayke († 767; feast: May 5), a priest and hermit in what is now Crayke, a village twelve miles north of York, famous for his holiness and gift of prophecy. The village has an Anglican St. Cuthbert’s Church, in which St. Cuthbert’s relics were once kept to save them from the Vikings;

—St. Elphin († c. 680), who was either British or Irish and may have been St. Oswald’s companion in Iona. When Oswald became King of Northumbria, he built a church for him in what is now the town of Warrington in Cheshire in northwestern England, where St. Elphin lived and was probably martyred. The medieval Anglican church, largely rebuilt in the nineteenth century, with a 281-foot spire, in Warrington, is dedicated to him;

—St. Hildeburgh, a seventh-century female ascetic who lived in what is now Hilbre Island (formerly St. Hildeburgh’s Island) off the northwestern tip of Wirral Peninsula in Merseyside (close to the River Dee estuary at the border between England and Wales) in northwestern England. She may have built a church or a convent there and lived as an anchoress. It became a place of pilgrimage, and in the Norman era there was a small community that was a dependent of Chester Abbey. A 1000-year-old cross head and another early cross shaft remind us of the site’s past. This island is the largest of three tiny isles off the Wirral. A modern Anglican church in the town of Hoylake in Merseyside on the coast of the Irish Sea is dedicated to St. Hildeburgh;

—St. Osanna of Howden, an obscure Northumbrian princess who probably lived in the eighth century and supposedly was buried at Howden Minster in the East Riding of Yorkshire. She was mentioned by the historian Gerald of Wales in the thirteenth century. According to him, centuries after her death the mistress of a secular canon of Howden Minster (a collegiate church; its clergy were to be celibate) one day sat on St. Osanna’s tomb and became immovable, with severe pain, covered in welts from an invisible flagellation. Only after many tears and sincere remorse was the woman released. The miracle contributed to an increase in Osanna’s veneration. After the Dissolution, much of Howden Minster in the town of Howden fell into ruin, and today its large nave is used as a parish church of Sts. Peter and Paul. A stained glass window of the 1950s in the minster is dedicated to Osanna. The minster has a fine medieval sculpture of the Mother of God with a dove.

These four saints are all but forgotten in our days. Finally, we would like to mention a post-Schism figure, who may have preserved Orthodoxy in those dark days after Norman invasion.

Godric of Finchale

Commemorated: May 21 (unofficially)

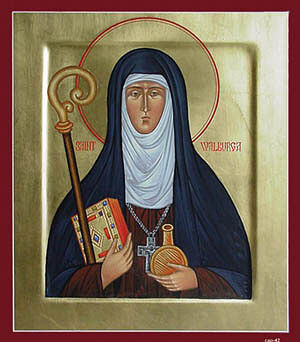

Godric of Finchale as depicted in an ancient manuscript, kept at the British Library (photo from Wikipedia)Godric (c. 1065–1169 or 1170) is the only Englishman living after the Norman Conquest who is included in our series of articles. There is a good reason for this. If he was never officially canonized by Roman Catholicism, it is surely because he remained authentically Orthodox in his spirit, way of life and form of piety. His life is little different from the Life of a Desert Father of the Orthodox East or, say, an early Irish or early English ascetic. Though Godric has been venerated only in Durham and Finchale four miles north of it, his biography is well documented and contains a wealth of interesting detail. There were several hagiographies of Godric written shortly after his repose, the best known was composed by his contemporary and disciple, Monk Reginald of Durham († c. 1190). In addition to his account of Godric’s life and posthumous miracles, Reginald also listed 130 miracles of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, and shorter accounts of Sts. Oswald of Northumbria and Ebba of Coldingham.

Godric of Finchale as depicted in an ancient manuscript, kept at the British Library (photo from Wikipedia)Godric (c. 1065–1169 or 1170) is the only Englishman living after the Norman Conquest who is included in our series of articles. There is a good reason for this. If he was never officially canonized by Roman Catholicism, it is surely because he remained authentically Orthodox in his spirit, way of life and form of piety. His life is little different from the Life of a Desert Father of the Orthodox East or, say, an early Irish or early English ascetic. Though Godric has been venerated only in Durham and Finchale four miles north of it, his biography is well documented and contains a wealth of interesting detail. There were several hagiographies of Godric written shortly after his repose, the best known was composed by his contemporary and disciple, Monk Reginald of Durham († c. 1190). In addition to his account of Godric’s life and posthumous miracles, Reginald also listed 130 miracles of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, and shorter accounts of Sts. Oswald of Northumbria and Ebba of Coldingham.

Godric, English by birth, was born in the village of Walpole in Norfolk in eastern England to a poor, religious family. His father’s name was Ailward, his mother was named Edwenna. In his youth he made a living as a peddler in Lincolnshire, then went to sea, became a ship’s captain and a “voyager” for about two decades, trading in Denmark, Flanders and Scotland. In those years he made a pilgrimage to Rome and another to the Holy Land. It may have been him—an English “pirate” Guderic (at that time the term “pirate” could mean “an independent seaman”)—who in 1102 snatched King Baldwin I of Jerusalem (who ruled from 1100–1118) to safety after his defeat at the Battle of Ramla, transporting him secretly from Arsuf to Jaffa. Making a good fortune in trading, Godric visited the great shrine of Santiago de Compostela and returned to his homeland, where he became a bailiff. Soon he made another two trips to Rome (on one occasion, with his mother) and visited the Abbey of Saint Gilles in France, founded by the great hermit St. Giles (the early eighth century; feast: September 1).

In about 1105, Godric gave away his fortune and tried to live as a hermit, inspired by the islands of Lindisfarne and Inner Farne, where St. Cuthbert had labored and appeared to him in a vision, suggesting he live the ascetic life. He first lived as a recluse in the woods and caves near Carlisle in Cumbria, reading his most favorite book, the Psalter, which he learned by heart. Soon he joined the aged hermit Aelric and spent some years with him at Wolsingham in Upper Weardale—now it is a little market town in County Durham in the northeast of England. In about 1110 he made another pilgrimage to the Holy Land, visiting its shrines, living with monks in St. John the Baptist’s Desert, working in a hospital, and constantly repenting of his past sins. Several months later he travelled back to England where he settled at an old hermitage near Whitby, then visited Durham Priory (which had St. Cuthbert’s relics), served as a doorkeeper at St. Giles’ Hospital in Durham, and attended the choir school at St. Mary-le-Bow Church in London.

The Finchale Priory ruins and the River Wear, Co. Durham (photo by Mat Fascione, Geograph.org.uk)

The Finchale Priory ruins and the River Wear, Co. Durham (photo by Mat Fascione, Geograph.org.uk)

Aged over forty, he settled near Durham, first at what is now St. Godric Garth, and finally in what is now Finchale Priory, making this place his home forever—for the remaining sixty years of his long life. This spot is still very beautiful and secluded, and it has not changed much over the past 900 years! Wooded and surrounded by the meandering River Wear from three sides, the spot, though four miles from Durham, was difficult of access and inhabited by numerous snakes, other dangerous animals and demons. Godric did very strict penance for his former sins for the rest of his life.

Spending all his time in fasting, prayer, repentance and piety, the saint acquired the gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, prophecy, clairvoyance, and miracles. He saw things happening at a distance and stopped storms at sea by prayer. Initially his diet consisted of berries, herbs, roots, nuts, acorns and wild honey, and he slept on the ground. Later, on the advice of a spiritual father from Durham (priests from Durham Priory visited him regularly) he began to grow vegetables and barley, which he milled, and baked bread for himself. The ascetic made himself a hermitage of branches and constructed a simple wooden chapel in honor of the Mother of God, with a cross, an icon of the Holy Virgin and a bell in it. At its corner, he had a “bath”—a barrel— of cold water where he used to wash. Like the Irish saints (and unlike later medieval monks), Godric used to pray all night long, immersing in the cold water of the River Wear or his barrel-bath. Over time, he built a small church in honor of St. John the Baptist, connected with the chapel by a thatched walk of wattle and daub. He wore a long beard, wore a hairshirt along with a metal breastplate and used a stone as his pillow.

His contemporaries described him thus: “He had a broad forehead, sparkling grey eyes and bushy eyebrows which almost met. His face was oval, his nose long, his beard thick. He was strong and agile, and in spite of his small stature his appearance was very venerable…He was eager to listen, but slow to speak; always serious, and sympathetic to those in trouble.”

There are many touching stories about his care for and affinity with wild animals (another attribute of Irish saints). In winter he would find freezing rabbits and mice, take them to his hut, warm them by fire and then let them run back. Snakes would often make themselves comfortable by his fire without doing him harm—his love extended even to such dangerous animals! Once Godric gave refuge to a stag chased by some hunters. When they reached his dwelling, they were amazed by his angelic countenance, apologized and left. Godric would scold bears who came to steal his honey (he kept beehives) or hares who ate his vegetables, and the animals obeyed him. Godric had a cow, which, at his command, would go to pasture every morning without a companion and come back in the evening at the proper time or return at the right moment when it was to be milked. The ascetic freed birds and other small creatures that had fallen into traps or snares.

Though Godric’s ascetic life was generally quiet, he was often tormented by demons, who used to steal his clothes while he was bathing. Once he was severely beaten and robbed by a band of Scottish raiders (Scots would attack the frontier regions of northern England due to conflicts between these countries), thinking that he had hidden “treasures”. On another occasion he almost died by the River Wear during a flood.

Seeing his holy life, kindness, love and extraordinary virtues, people began to flock to Godric, seeking counsel, consolation and healing. Among his guests were the Cistercian Abbot Ailred of Rievaulx (a writer and prominent hagiographer), Prior Laurence of Durham (a poet and hagiographer, who composed one version of the Life of St. Brigid), Abbot Robert of Newminster (a co-founder of Fountains Abbey), the Augustinian canon William of Newburgh (an important historian and chronicler) and William I the Lion (King of the Scots 1165–1214). In the first years of his solitude his mother and brother also came to live nearby. Reginald of Durham, mentioned above, tended to Godric towards the end of his life, when he was weak and sick. Godric received messengers from Archbishop Thomas Becket of Canterbury (whose martyrdom he predicted) and Pope Alexander III, who asked for his (Godric’s) prayers.

One of the most remarkable things about Godric is that though he had never been able to compose hymns, the Mother of God appeared to him, rewarded him with this talent and taught him a particular hymn that should be sung in sorrow, pain or temptation. He had a vision of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, who had certainly helped him in his seafaring years. His sister Burchwen, who led an ascetic life close to him and then moved to Durham to work at a hospital, also appeared to him, surrounded by angels, at the moment of her death, singing another hymn that he wrote down. Not only did Godric compose verses, he also set them to music. His three verses survive and are sometimes used by the faithful. In translation into modern English, they sound like this:

1. The Song that the Mother of God taught him:

Saint Mary, Virgin,

Mother of Jesus Christ of Nazareth,

Receive, shield, help thy Godric;

Received, bring him on high with thee in God’s kingdom.

Saint Mary, bower of Christ,

Purest of maidens, flower of mothers,

Blot out my sins, reign in my mind,

Bring me to joy with that same God.

2. A Prayer to St. Nicholas, inspired by the saint’s vision:

Saint Nicholas, God’s beloved,

Build for us a fair bright house;

At birth, at the bier,

Saint Nicholas, bring us safely there.

3. The Song sung by his sister as she was ascending to Heaven:

Christ and Saint Mary so carried me with a crutch

That I never had to tread upon this earth barefoot.

The Finchale Priory ruins, Co. Durham

The Finchale Priory ruins, Co. Durham

Godric reposed on May 21, 1170, at the great age of 105. He was venerated as a saint and wonderworker, and his name can be found in the calendars of Durham and some Cistercian abbeys. At first his relics rested at Durham Priory, but later they were translated back to Finchale. In 1196, a Benedictine priory was founded in Finchale on the site of his ascetic labors and became a dependency of Durham Priory. Finchale priory was prosperous for many years, gaining its wealth thanks to pilgrims—though the community was always small. In the late Middle Ages it grew poor and became a retreat for Durham monks. The priory was dissolved in 1538 and gradually reduced to ruins. The priory remains are in the care of the English Heritage foundation. By the scale of its ruins we can judge how extensive the Priory was. Among the surviving ruins are standing walls, fragments of the church, claustral and farm buildings and some decorations. The objects of note include the foundation of St. John’s Church built by Godric, with a simple stone cross near it marking Godric’s possible grave, which was near the high altar. This tranquil and idyllic place would be perfect for a hermit even today…

One of the paintings of Godric is in a fourteenth century manuscript, now in the British Library, containing a poem about ascetic life and illustrated with images of hermits. Godric is depicted there kneeling in prayer, with the Mother of God with her Child above him, teaching him to write her song. Godric is usually depicted in white garments as an old hermit, kneeling in prayer, with a stag at his feet.

There is a Catholic Church of Our Lady of Mercy and St. Godric in the city of Durham.

Holy Alkelda, Everilda, Herbert, and all the saints of northern England, pray to God for us!

4/21/2021