I THINK I WOULD BECOME A PRIEST IF I WERE EVER RELEASED”

The life of Ioan Ianolide, who spent twenty-three years in prison for Christ. Part 3

Part 1. The The Life of Ioan Ianolide

The second trial

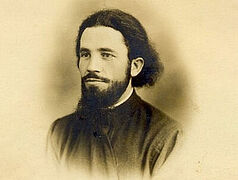

Ioan Ianolide. Photo attached to the interrogation protocol, 1958

Ioan Ianolide. Photo attached to the interrogation protocol, 1958

After the Soviet troops left Romania in 1958, the Securitate (the Department of State Security) hastened to launch a new wave of arrests to prevent the population from revolting against the “people’s democracy”. Many “enemies of the people” imprisoned in the first wave of arrests in 1948 had already been released, and the Communist Party was eager to send them back to the siguranță.1 So the Securitate tried to extend the terms of those who hadn’t yet been released. This explains why on a cold autumn evening of 1958, Ioan was taken from Aiud to Bucharest for new interrogations. He once again had to go through terrible torture and bitter humiliation.

There were mainly two charges against him: that he had allegedly put together a gang of Legionnaires in Targu Ocna Hospital and ordered those who were released to maintain the organization’s combat capability and arrange a counter-revolution against the “working class”.

The charges were absurd. The most natural Christian practices that he and other confessors performed at Targu Ocna were declared by the Securitate as “Legionnaire activities.” So during interrogations, Ioan was surprised to hear that “a wedding can be called a ‘counter-revolutionary Legionnaire meeting’, a baptismal gift, ‘Legionnaire assistance provided for anti-State purposes’, and a pilgrimage to a monastery, a ‘Legionnaire training campaign with the aim of seizing political power’, and many similarly absurd interpretations.”

Another serious charge against Ioan was the twelve Christian principles that he had formulated at Targu Ocna and then used to lift the spirits of inmates in the prisons he would go to. Written down by Priest Constantin Voicescu after his release on a book that had been confiscated from him in 1959 during a new arrest, these principles were also classified by the Securitate as Legionnaire:

“A copy of the instructions on Legionnaire activities elaborated by the defendant Ion Ianolide, distributed among the Legionnaires and restored in 1954 by the defendant Constantin Voicescu and Vasile Petrescu on the pages of Simion Mehedinţi’s book, Trilogies.”

In fact, these principles, full of theological depth, were compiled by Valeriu together with Ioan on the basis of the spiritual experience accumulated by them over the years of suffering.

But the Securitate regarded Valeriu and Ioan as the leaders of the “mystical” atmosphere created at Targu Ocna, and since Valeriu was dead, the burden of accusations of “intrigues” now fell on Ioan’s shoulders. After five months of exhausting interrogations Ioan fell into a miserable state, and so he was sent for rehabilitation to the Văcărești Prison hospital2. This measure, of course, wasn’t taken for reasons of humanity, but so that no traces of inhuman treatment could be seen on him at the trial.

Interior of the Văcărești Prison church

Interior of the Văcărești Prison church

When he was taken to court at the Bucharest Military Tribunal, he finally had the opportunity to see his parents after years of separation. But when they led him past his mother, she didn’t even recognize him and exclaimed:

“Whose’s this one, the poor thing?!”

He was so mutilated and disfigured that his own mother didn’t recognize him.

When given a word to say, Ioan confessed:

“I discussed Christian matters with all the prisoners. There was not a single inmate with whom I didn’t discuss Christian problems and principles. I think I would become a priest too, if I were ever released.”

Moreover, he took it upon himself to defend all the prisoners:

“None of the defendants are guilty! Give these people freedom, let them return to their families!”

Bucharest Military Tribunal

Bucharest Military Tribunal

But of course, sentences came one after the other, because it was a mock and the decisions had been prepared ahead of time; so twenty-nine people were immediately sentenced to terms ranging from fifteen years to life with forced labor. They were again thrown into prison for the same reason—their confession of Christ. The terrorist regime couldn’t forgive them this, particularly Ioan who was sentenced to another twenty-five years of forced labor.

At Jilava

In April 1960, Ioan was sent to Jilava Prison, to the hell of the terrible butcher Maromet. On the transfer card, in the “degree of danger” column, highlighted in red and circled were the words, “Attention! A very dangerous Legionnaire!” Meek and innocent, Ioan was declared socially dangerous. Pious and well-mannered, he “posed a great threat to the social order.” But the Securitate was right in its own way, because in those days the confession of Christ posed a mortal danger to Communist atheism.

Jilava, maximum security prison. Photo: Daria Raducanu

Jilava, maximum security prison. Photo: Daria Raducanu

On his arrival, Ioan was thrown into one of the most overcrowded Jilava torture chambers. George Ungureanu, one of the sufferers who was sitting in the cell when Ioan entered, later wrote that “one evening, before food was served, a prisoner was brought into the chamber—tall, handsome, with a bundle under his arm and a bloodstained handkerchief at his mouth:

‘Do you see him?’ the guard shouted from the doorstep. ‘He has been imprisoned for over twenty years and is sick. He needs a plank-bed beneath a window!’

‘My name is Ioan Ianolide. I have been in prison since 1941, since my student years. I have tuberculosis, I spit blood. Look.’ He showed us his handkerchief and then proceeded, ‘Besides, I have another disease: I cannot keep my balance. They used to hit me on the head and I shake continuously! Is there a priest among you? If so, I ask him to bless me!’

‘Lord, bless brother Ioan who is now one of us!’ Priest Buzău Popescu exclaimed.

“After this blessing, there was commotion in the cell for several minutes. None of the prisoners wanted to sacrifice their place to Ioan who desperately needed air to dull the symptoms of tuberculosis. Ianolide, having seen enough of all sorts of squabbles over the years of his imprisonment, sat down calmly on the bed of Romeo Pușcașu next to the door.

“Ioan Ianolide had spent over twenty of his thirty-eight years in Romanian prisons, but he did not lose two great gifts of God: spiritual and physical beauty. Alongside the other prisoners he looked like a saint, although over two decades he had gone through all the tortures that the devilish mind of evil people could invent, cold and hunger, war and death, typhus and tuberculosis.

“Such tortures cannot be compared with those of the first Christians, who were burned alive and fed to wild beasts; but still, they suffered for several minutes and died, whereas Ioan was tormented for decades.

“When quarrels or conversations began in the cell, Ianolide would withdraw into himself and read psalms without losing peace of mind. He was a model of life in a prison, living with a halo of holiness.”

He stayed at Jilava until November 1960, when he was sent to Gherla Prison, and then again sent to Aiud Prison.

Hopelessly sick and incapable of being re-educated

In 1962, the last wave of “re-education” of political prisoners began. Then the ruling party, under pressure from international forces, had to release political prisoners. But since the princes of this world were afraid to release “class enemies” without breaking them, the last stage of re-education of political prisoners was launched. The inhuman process of mutilation of souls was led by Colonel Gheorghe Crăciun, head of Aiud Prison from 1958 to1964.

The methods were much milder than at Pitești Prison, but the goal was the same. Instead of torture and violence they promised to release prisoners if they agreed to cooperate, and in case of refusal they resorted to starving, isolation and blackmail. They began to open cultural and educational clubs, where “cultural” education meant re-education in the spirit of Marxism and Communism.

Ioan was also subjected to the re-education process, but remained unaffected by the last diabolical onslaught and was never “re-educated.” This is demonstrated by the description given by Colonel Crăciun in July 1963:

“In general, this type is unyielding and fanatical. Starting from 1962, he became involved in cultural and educational work, but from the very beginning he took a clearly hostile position towards cultural work. At the present time he adheres to the same position, which allows no concessions, exerting a negative influence on fellow inmates. He is no longer involved in work.”

Subsequently, pressure was stopped, because he was taken to the eleventh tuberculosis department as “hopelessly ill and bedridden.”

“Release” to the giant prison of Romania

Finally, in 1964, a decree on a general amnesty for political prisoners was issued. But prisoners were told that they wouldn’t be released unless they were re-educated. It was a desperate attempt by the regime to muddle the minds of the martyrs at the last moment. And yet, during July, groups of sufferers left the hell of Aiud, and on July 31 Ioan was given a certificate of release and a train ticket to Bucharest. “I was shocked and wept bitterly,” Ioan recalled those moments of mental shock.

Thus, after twenty-three years of indescribable suffering, with joints stiff from rheumatism and tuberculosis, Ioan left his last prison to enter the giant prison of Communist Romania. Not knowing who he would see in his house, he decided to go to his aunt first. Throughout the journey he wept, thinking about the terrifying prospects opening up in a Communist society.

Having alighted at the North Railway Station, he looked around for his fiancé, but neither she, nor anyone else was waiting for him. No one needed him, and he was a nobody among strangers.

North Railway Station in Bucharest. Photo: Daniel Branishtyan

North Railway Station in Bucharest. Photo: Daniel Branishtyan

Finally, together with an ex-fellow prisoner, he reached his aunt. He was received with a storm of emotions and a sea of tears, but the joy was short-lived as the final blow awaited him. He learned that his mother had passed away three years before, and his ex-fiancé Valentina had married another man a year before after waiting for him for eighteen years and not knowing whether he was still alive. Ioan’s heart nearly broke at that news.

“I writhed all over and burst into a voiceless cry that will never subside in my soul. Everything collapsed and turned into ruins, and I was turned into a ghost, a chimera. But I relied on the will of my relatives. And hand in hand with two old people I entered a new, hostile, devastated world.”

Soon he was admitted to a hospital for rehabilitation, and soon Valentina came to see him. She said that she would divorce her husband and return to him. But Ioan refused, considering the sacrament of marriage higher than betrothal. Once again he gave up all the best he had in life for Christ’s sake.

After regaining some strength, he wanted to enter a monastery, but the authorities who controlled monastic life did not allow him to do it. And God hastened to send him a wonderful wife for his endless suffering. A year after his release, Ioan married Constanța, who selflessly took care of him till his last breath.

Ioan and Constanța Ianolide, 1965

Ioan and Constanța Ianolide, 1965

To earn a living, he got a job first at the laboratory of the Geological Institute of Romania, and then at a cooperative for the production of artwork, and worked from home.

Ioan cautiously tried to share the ideas he was burning with, but in the atmosphere of terror dominated by an anti-religious mentality implanted by the Communists he found a very small audience. Then he tried to move abroad, but he was denied a foreign passport and wasn’t allowed to leave the country.

So he had to live in a world hostile to his sensitive soul, bearing the stigma of an “enemy of the people.” He couldn’t defend himself from this humiliation in any way and silently forgave everyone. Hurt by the incessant carping of the “working people,” he withdrew into himself and devoted all his time to prayer and carving crosses, icons, and other religious items.

Final years of his life

Although the Securitate watched him vigilantly, intrigued against him and threatened him with death, Ioan decided to risk everything again and leave a written testimony about what he had seen and experienced in Communist prisons. For three years, from 1981 to 1984, under constant fear of being caught by the Securitate, he filled hundreds of pages with bitter memories from the depths of his holy soul.

To avoid being exposed he made himself three lamps with wooden boxes decorated with plastic ornaments at the base of each one. Into them he inserted other, smaller boxes made of tin, into which he hid each page as soon as he finished it. On one of these pages he made the following remark:

“I wrote in a hurry, furtively, on my own and without corrections. Please proofread my writing. I had no documents, no friends with whom I could consult, and I could not even reread what I had written, because once each sheet was filled, I hid it securely.

“I wrote this as a confession. I wrote this as a testament. I wrote in the hope that these lines would outlive me.”

Ioan Ianolide

Ioan Ianolide

When he completed this last confession of faith, God called him to eternal rest. Shortly after his retirement he contracted cirrhosis, and then a neoplasm appeared on his internal organs, which put an end to the earthly stage of his existence.

Thus, after a life entirely devoted to God, Ioan fell asleep in the Lord on February 5, 1986. His body, which had suffered indescribable torments, rests in the cemetery of Cernica Monastery not far from the grave of his father-confessor whom he found after his release, the bright Fr. Benedict Ghiuș.

Ioan Ianolide’s grave in the cemetery of Cernica Monastery, Bucharest

Ioan Ianolide’s grave in the cemetery of Cernica Monastery, Bucharest

One of his last desires was that at his funeral, those who wished would receive the ladanka amulets3 and crosses, which he used to make until his eyesight failed. This was Ioan’s most powerful word to our people: “Bear your cross!” However, the high motto of his whole life is engraved on his grave cross: “All in Christ”.

After his repose

Most of the manuscripts that Ioan wrote in that atmosphere of terror were sent to the West in the hope that they could be published there. In the end, through Fr. Constantin Voicescu’s efforts, after the 1989 Revolution they were returned to their homeland, and then, by Divine Providence, ended up in Diaconești Monastery. Here for two years the manuscripts were carefully put in order, corrected, and as a result they compiled a book entitled, Return to Christ: A Document for a New World.

Diaconești Monastery

Diaconești Monastery

Ioan’s witness contained in it is amazing. It shakes your soul, because after reading these pages you can’t remain as you were before. The power of his witness brings us closer to Christ, for in it a voice cries out from holy prisons, calling to all generations till the end of the age: “Return to Christ—this is the only chance for mankind to be saved.”

Although he lived in the world as a nameless person whom “no one knew but prison”, the light that he left in history and the spiritual labor that yielded fruit after his death give us the right to say that Ioan Ianolide’s life is an ideal of Christian perfection, and he is our intercessor in Heaven in the host of saints who suffered in the prisons.

Rejoice, O blessed Ioan, long-suffering one of God!

Mărturisitorii (Confessors)

11/16/2022

1 The secret police in Romania under the king was called Siguranța (Rom. “security”), it operated from 1921–1944. Under socialism its successor was the Securitate, the department of state security that existed from 1948–1989.

2 The ancient Văcărești Monastery was converted into a prison in 1848. Nevertheless, the magnificent church remained active, and prisoners were its parishioners until 1987, when it was demolished.

3 Ladanka is a tiny cloth bag, usually worn around the neck with a cross, and used for carrying a tiny amount of incense, a prayer written on paper, a particle of relics, or soil from a holy site. They are widely used by lay-people in Russia and several other Orthodox countries.—Trans.

Commemorated February 5/18

Among the many portraits of the confessors, one will be found in particular that is recalled with reverence by all and is considered a saint: Valeriu Gafencu. Nicknamed “the saint of the prisons” by Father Nicolae Steinhardt in a truly inspired moment, Valeriu Gafencu was one of the more impressive figures who lived an admirable spiritual life amidst prison conditions.